| Home | Information | Contents | Search | Links |

|

I knowed a mighty likely pilgrim, jest from

the states. Plucky? That warn't no name for

it! An' knowledgable? Waal, sir, he could

chin it with ary preacher you ever see! I

reckon, if he'd sot his mind to it, he could

'a' wrote a book that two men couldn't pack.

P. S. WARNE, The Gentleman from Pike, 2

Edward Lytton Wheeler, self-styled "Sensational Novelist," whose heroic "Deadwood Dick" is better known to fame than his creator, is another author about whom even the newspapers, which so often refer to this character, seem to know very little. Nowhere has any biography been found, and the meager sketch below has been pieced together from bits of information gathered here and there, the greater part from a few letters written by Wheeler himself.

Edward Lytton Wheeler(1) was born in Avoca, New York, in 1854 or 1855.(2) From that town his parents, Sanger Wheeler (the sixth child of George and Gratia Steams Wheeler) and his wife Barbara Lewis, a daughter of Herman and Margaret Thompson Lewis,(3) removed in the early 1870's to Titusville, Pennsylvania, famous as being the town where, in 1857, the first oil well in the United States was drilled. Here the Wheelers kept a boarding house.(4) They removed to Philadelphia in 1875, where, during the Centennial, they also kept boarders.

Edward's father must have died about this time, for in the Philadelphia City Directory for 1877, his mother is listed as a widow.(5)

In the middle 1870's Edward began writing for the story papers, and had short sketches in the Saturday Journal in 1877 †and later.(†6) His first novelette appears to have been "Hurricane Nell, the Girl Dead-Shot; or, The Queen of the Saddle and Lasso," published as No. 1 of Starr's Ten Cent Pocket Library, May 4, 1877. Rapidly following this came No. 3 of the same series, "Old Avalanche, the Great Injun Annihilator; or, Wild Edna, the Girl Bandit," June 15, 1877, and No. 6, Starr's New York Library, "Wildcat Bob, the Boss Bruiser; or, The Border Bloodhounds," July 25, 1877. He had the honor of writing the opening number of the Half-Dime Library, October 15 of the same year, his famous first episode of the adventures of "Deadwood Dick."

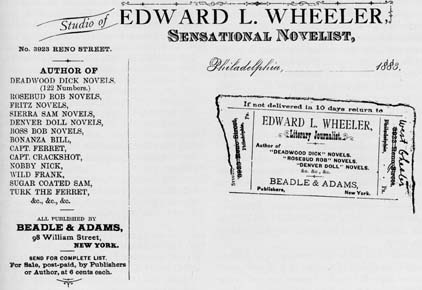

With a brilliant start as a writer, he was married May 12, 1878, to Miss Alice Eager, of West Philadelphia,(7) and in the same year returned to Titusville.(8) According to his own letter, he was then making about $950 a year, which he thought "pretty good, considering the hard times." He was still in Titusville at least until December 30, 1878,(9) but shortly thereafter he and his wife were back in Philadelphia. For a brief period in 1880,(10) Wheeler managed a theatrical company, probably featuring his own play, "Deadwood Dick, a Road Agent. A Drama of the Gold Mines."(11) Apparently it was unsuccessful (though later in the decade it reappeared on the New York stage) for in the autumn of 1880 Wheeler resumed his regular contributions to the Beadle publications, In 1884 he lived in West Chester, twenty-seven miles from Philadelphia, and as he himself wrote to Mr. Locke,(12) a boyhood friend from Titusville, he was still "engaged in the old business of 'sending boys out west to kill injuns,' as the unco' good newspaper editors have it," and at that time he had one child living, a boy a year old. Apparently he had his office in Philadelphia, for the letterhead reads "Studio of Edward L. Wheeler, Sensational Novelist †3923 Reno Street, Philadelphia, 1883," and the Philadelphia Directory(13) lists him as at 4020 Lancaster Avenue. The last Philadelphia Directory listing Wheeler is the one for 1885, but the appearance of ninety-seven Deadwood Dick, Jr., stories in the Half-Dime Library between 1885 and 1897 seemingly suggests that he was still actively engaged in writing.

During these years, Beadle and Adams, in the Banner Weekly, published no personal news whatsoever about Wheeler, and no word leaked out, even to other Beadle authors, that Wheeler had died. There were rumors that he went west to Chicago and later was down and out. It is true that three Edward L. Wheelers are listed in the Chicago Directories. Two of these are definitely ruled out, for one came to Chicago too soon and the other too late, and none is listed as a writer. On the other hand, the evidence of the Philadelphia Directories that Wheeler died in 1885 or 1886 appears to be incontrovertible. Wheeler himself was listed at 3604 Failmount Avenue in 1885, and in 1887, at the same address, appeared the name of Alice Wheeler only. It is not at all likely that Edward's name would have been omitted and Alice's name substituted if he were still at that address, and his death late in 1885 or early in 1886 seems to be confirmed by the listing of Alice Wheeler as the "widow of Edward L." in the Directory for 1891 and following. What, then, is the meaning of the ninety-seven Deadwood Dick, Jr., stories that appeared with Wheeler's by-line between 1886 and 1897?

If we examine all of Wheeler's publications, a startling fact is brought out, which almost definitely fixes his death in 1885. Of publications not reprints, there appeared in the Half-Dime Library in:

1877 2 Deadwood Dick stories only.

1878 6 Deadwood Dick stories and 7 not Deadwood Dicks.

1879 4 Deadwood Dicks and 9 others.

1880 4 Deadwood Dicks and 5 others.

1881 5 Deadwood Dicks and 4 others.

1882 3 Deadwood Dicks and 9 others.

1883 2 Deadwood Dicks and 8 others.

1884 3 Deadwood Dicks and 12 others (of which 4 were in the Banner Weekly)

1885 4 Deadwood Dicks and 9 others (of which 2 were in the Banner Weekly)

The original Deadwood Dick stories ended October 20, 1885, with the death of the hero in Half-Dime Library No. 430. Two other Wheeler stories (Half-Dime Library No. 434 and Half-Dime Library No. 438) were issued in 1885, but on January 19, 1886, the Deadwood Dick, Jr., stories, still with the by-line Edward L. Wheeler, began in the same "library," and suddenly other stories by Wheeler ceased to appear. There is not a single original Wheeler story except those relating the adventures of Deadwood Dick, Jr., during the entire time, while previously those of other types outnumbered the Deadwood Dicks. Another noteworthy point is the fact that †some of the Deadwood Dick, Jr., stories were much less well written than the original Deadwood Dicks, both in words and plot. This let-down in the quality of the stories was noticed by John H. Whitson, who re-wrote some of them at the request of the publishers, but had no knowledge of Wheeler's death and ascribed it to a physical break-down of the author. Since the Deadwood Dick stories were extremely popular, Beadle and Adams naturally wished to continue them, and it is certain that they employed †one or more ghost-writers †.

The only name under which any of Wheeler's stories were reprinted was "Edward Lytton," and all of these had been published originally before June, 1885. †At least twenty-five (the sixty-first to the eighty-fifth) and probably more of the Deadwood Dick, Jr., stories were written by Jesse C. Cowdrick. Whitson wrote some of the earlier ones, but who wrote the earliest is unknown. See under Cowdrick in this supplement (Vol. II, pages 69—70).

Wheeler had more the appearance of a theological student than of a writer of wild and wooly Western tales. He wore a Stetson hat, and is said to have greeted even strangers as "pard," which may not, after all, have been a mannerism, but a habit acquired among the oil men with whom he associated in his boyhood days. The statement made by Edmund Pearson(13) that he had never been farther west than Jersey City, is, of course, incorrect, for even Titusville is over 300 miles west of that city.

Wheeler had a sense of humor and was not a bad rhymester. The geography of some of his tales is a bit wild. Cheyenne, for example, lay to the east of the Black Hills, and the topographic features described by him near Deadwood do not exist. His San Juan topography also is very inaccurate. On the whole, however, his descriptions are convincing—if one is not personally familiar with the localities and is not too critical.

Ave atque vale.

REFERENCE: Practically everything that is known is cited in the footnotes above.

The ghost written stories with the Wheeler by-line are listed here with his own. They are numbered 443 to 1018; No. 1001 only is a reprint. †Cowdrick's identified stories are Half-Dime Libraries Nos. 792 to 940 of the list below with the exception of Nos. 913 and 922, which are reprints of earlier numbers.

Starr's Ten Cent Pocket Library. Nos. 1, 3

Saturday Journal. No. 450

Beadle's Weekly. Nos. 62, 72, 77, 87, 118, 128 (fartim), 132

Banner Weekly. Nos. 411, 417, 423, 566

Starr's New York Library. No. 6

Dime Library. Nos. 6, 1034

Half-Dime Library. Nos. 1, 20, 26, 28, 32, 35, 39, 42, 45, 49, 53, 57, 61, 69, 73, 77, 80, 84, 88, 92, 96, 100, 104, 109, 113, 117, 121, 125, 129, 133, 138, 141, 145, 149, 156, 161, 177, 181, 195, 201, 205, 209, 213, 217, 221, 226, 232, 236, 240, 244, 248, 253, 258, 263, 268, 273, 277, 281, 285, 291, 296, 299, 303, 309, 321, 325, 330, 334, 339, 343, 347, 351, 358, 362, 368, 372, 378, 382, 385, 389, 394, 400, 405, 410, 416, 421, 426, 430, 434, 438, 443, 448, 453, 459, 465, 471, 476, 481, 486, 491, 496, 500, 508, 515, 522, 529, 534, 539, 544, 549, 554, 561, 567, 572, 578, 584, 590, 595, 600, 606, 612, 618, 624, 630, 636, 642, 648, 654, 660, 666, 672, 678, 684, 690, 695, 700, 704, 710, 716, 722, 728, 734, 740, 747, 752, 758, 764, 770, 776, 782, 787, 792, 797, 802,807, 812, 816, 822, 828, 834, 840, 845, 852, 858, 863, 870, 876, 882, 891, 898, 904, 910, 913, 916, 922, 928, 934, 940, 943, 946, 951, 957, 965, 971, 977, 986, 992, 998, 1001, 1005, 1011, 1018, 1057, 1090, 1119, 1120, 1130

Boy's Library (quarto). No. 21

Boy's Library (octavo). No. 6

Pocket Library. Nos. 1, 4, 7, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, 30, 33, 37, 41, 45, 53, 57, 61, 64, 68,73, 76, 78, 83, 88, 94, 96, 99, 103, 107, 111, 115, 119, 123, 127, 131, 135, 141, 147, 153, 158, 163, 168, 175, 188, 193, 205, 212, 218, 225, 231, 236, 241, 247, 252, 258, 264, 270, 276, 282, 288, 294, 300, 306, 312, 318. 324, 330, 336, 343, 350, 356, 362, 368, 374

Popular Library. No. 43 (partim)

Under the name "Edward Lytton" were published:

Popular Library. Nos. 7, 11, 17, 24, 31

Half-Dime Library. Nos. 1079, 1087, 1093, 1097, 1105

SPECIMEN OF EDWARD L. WHEELER'S STYLE

"Deadwood Dick, the Prince of the Road; or, The Black Rider of the Black Hills." Half-Dime Library No. I, pp. 2-3, 4.

"$500 Reward: For the apprehension and arrest of a notorious young desperado who hails to the name of Deadwood Dick. His present whereabouts are somewhat contiguous to the Black Hills. For further information, and so forth, apply immediately to

HUGH VANSEVERE,

At Metropolitan Saloon, Deadwood City."

Thus read a notice posted up against a big pine tree, three miles above Custer City, on the banks of French creek. It was a large placard tacked up in plain view of all passers-by, who took the route north through Custer gulch in order to reach the infant city of the Northwest —Deadwood.

Deadwood! the scene of the most astonishing bustle and activity this year (1877). The place where men are literally made rich and poor in one day and night. Prior to 1877 the Black Hills have been for a greater part undeveloped, but now, what a change! In Deadwood districts every foot of available ground has been "claimed" and staked out; the population has increased from fifteen to more than twenty-five hundred souls.

The streets are swarming with constantly arriving new-comers; the stores and saloons are literally crammed at all hours; dance-houses and can-can dens exist; hundreds of eager, expectant, and hopeful miners are working in the mines, and the harvest reaped by them is not at all discouraging. All along the gulch are strung a profusion of cabins, tents and shanties, making Deadwood in reality a town of a dozen miles in length, though some enterprising individual has paired off a couple more infant cities above Deadwood proper, named respectively Elizabeth City and Ten Strike. The quartz formation in these neighborhoods is something extraordinary, and from late reports, under vigorous and earnest development are yielding beyond the most sanguine expectation.

The placer mines west of Camp Crook are being opened to very satisfactory results, and, in fact, from Custer City in the south, to Deadwood in the north, all is the scene of abundant enthusiasm and excitement.

A horseman riding north through Custer gulch, noticed the placard so prominently posted for public inspection, and with a low whistle, expressive of astonishment, wheeled his horse out of the stage road, and rode over to the foot of the tree in question, and ran his eyes over the few irregularly-written lines traced upon the notice.

He was a youth of an age somewhere between sixteen and twenty, trim and compactly built, with a preponderance of muscular development and animal spirits; broad and deep of chest, with square, iron-cast shoulders; limbs small yet like bars of steel, and with a grace of position in the saddle rarely equaled; he made a fine picture for an artist's brush or a poet's pen.

Only one thing marred the captivating beauty of the picture.

His form was clothed in a tight-fitting habit of buckskin, which was colored a jetty black, and presented a striking contrast to anything one sees as a garment in the wild far West. And this was not all, either. A broad black hat was slouched down over his eyes; he wore a thick black vail over the upper portion of his face, through the eye-holes of which there gleamed a pair of orbs of piercing intensity, and his hands, large and knotted,(14) were hidden in a pair of kid gloves of a light color.

The "Black Rider" he might have been justly termed, for his thoroughbred steed was as black as coal, but we have not seen fit to call him such—his name is Deadwood Dick, and let that suffice for the present.

"Jack Hoyle, the Young Speculator; or, The Road to Fortune." Half-Dime Library No. 113, pp. 3, 5.

The first day of Jack's travel revealed no incident worthy of record, and he slept in a haymow at night.

In the morning, he asked for one cent's worth of milk of a dairyman, and the man being of a liberal turn of mind, dealt out a quart of his richest and some bread in the bargain.

While Jack was eating his meal upon the doorstep, he noticed a swarm of cats, twenty or thirty, come from the woods in a sort of procession, each one carrying in its mouth a chipmunk, or a bird, or a field-mouse.

"Pretty good cats," Jack remarked, to the dairymaid.

"Och! yis, sur," she replied, "niver a foiner lot of cats is there in the world."

When the farmer came along, again, Jack said to him:

"A fine lot of cats, sir."

"Humph! I wish some fellow'd take the job of drownin' the ravenous things," was the reply.

"I'll buy them of you, if you will sell them reasonably," Jack said.

"All right, young feller—what'll you give for the lot —twenty-five cents?"

"Just fifteen cents, and you deliver 'em to me, in Boston."

"Agreed! Am goin' to town, to-night. Where shall I leave 'em?"

Jack named the store of an acquaintance. "I will be there when you come."

"Mebbe 'tain't none o' my business, young feller, but what are you going to do wi' them serenaders?"

"Speculate on 'em," Jack replied, as he took his departure.

Striking cross lots from the farm-house, he struck the Boston, Lowell and Nashua railroad, and following the track, reached the city of Boston early in the afternoon, without a penny in his pocket.

But not despairing, he wended his way to Beekman's storehouse in Congress street, and found his college chum. Bob Beekman, in attendance.

The greeting between the two young men was warm, and after some conversation, Jack succeeded in borrowing ten dollars of Bob, and also a corner in the warehouse in which to leave his cats.

He then visited several of the leading newspaper offices, and contracted for an advertisement something after this pattern:

"AN EXTRAORDINARY NOVELTY." "Just received at Beekman's warehouse, in Congress street, an importation of the celebrated Belgium mousers—the best breed of game-hunting cats in existence. The only ones in this country for sale. Call early for a choice.

(Signed) Monsieur Johan Holle."

This done, Jack returned to the warehouse.

Just at dusk, farmer Duncan drove up with a crate full of cats, and after receiving the cats, and storing them in the warehouse for the night, Jack sought out a cheap hotel, procured a "square" meal and lodging for the night.

Early in the following morning he was at the warehouse, with shears and ribbons, and soon had the Thomas cats satisfactorily clipped and named, with ribbons about their necks, and the whiskers closely clipped from the females, to give them an odd appearance.

He then arranged them upon benches, and by the time he was ready, curious people began to drop in to see the cats.

There were cats of both sexes and all colors and temperaments, from the humped-back, prowling Thomas to the purring domestic, and altogether they were an intelligent looking lot.

The forenoon passed and though many visitors called, none seemed disposed to invest; not a sale was effected.

After dinner, as he was wondering if he had not made a disastrous failure, Jack was electrified to see Mr. Lome and his daughter, of Lowell, drive up to the storehouse, and get out.

Quickly substituting Bob Beekman as salesman. Jack retired behind some drygoods boxes, for he had no desire to meet the haughty Miss Lillian in his capacity of cat-vender.

The Lornes entered, and Bob graciously showed them the cats, pointing out the extraordinary merits of each animal, and "cheeking" his way right into the confidence of the Lowell financier.

"If you want cats," said Bob, with great importance, "now is your time to get one of the celebrated breed of mousers, as it is doubtful if the Belgian Government will allow Monsieur Holle to bring over another importation. There is the red female cat, with the almond-eyes, warranted to be a thoroughbred hunter, and also a pet family cat of cleanly habits. That is the flower of the cat flock—price $200. Any of the others we will let go for one hundred and seventy-five, cash."

"The price is exhorbitant," Lome said, reflectively, "but I believe I will take the reddish cat. Can you box it and send it to Lowell, by express?"

"Oh! certainly," Bob hastened to say. "It will reach you on the first train."

Accordingly the Lowell financier paid the two hundred dollars, left his address, and then drove away.

After they had gone, Jack emerged from his concealment, and collared Bob.

"Bob Beekman, you are a rascal!" he exclaimed, laughing. "I should have sold any cat in the flock for ten dollars."

"And made a goose of yourself," Bob replied. "Such men as Lome always pay for being rich."

Toward evening an old lady from the country hobbled in, and viewed the cats, with evident admiration. Her fancy seemed to be set upon one striped feline of serenading proclivities.

"Let me sell you that mouser, ma'am," Jack said, courteously. "You're an old lady: we'll sell you that cat for ten dollars. Good mouser; eats whatever you give her, and a faithful family cat."

"Well, well. That's a big price, but I want jest sech a cat. Take nine dollars fer it?"

"Yes—give us the cash, and take the cat."

The old lady paid that sum and tucking Thomas under her arm, hobbled out.

She had not got off the platform, when Bob and Jack saw farmer Duncan rush up to her, excitedly.

"For Lord's sake, mother, what are you doing with that cat?" he was heard to exclaim.

"Cat?" the old lady exclaimed, proudly; "why, Josiah, that's one o' the Belg'um mousers, w'at ar' advertised in ther Transcript. Old Lome, up at Lowell got one, an' paid two hundred dollars fer it, an' this animal only cost me nine dollars."

"You old fool!" the farmer exclaimed, aghast. "That's one of our own cats, what I sold last night to that chap in the storehouse for less than a cent apiece. And he's beat you clean out o' your eyes!"

"No, he hasn't!" stoutly averred the old lady. "That cat cum frum Belg'um. Didn't I read about et in the Transcript? I reckon yer mother knows what she's about, Josiah Duncan. I 'arned thet nine dollars a-pickin' berries, an' ef I want ter buy cats with it, I'm a goin' ter buy cats. Come, start along, and don't make a monkey of yourself here before folks."

The old lady won the day, and the farmer went away with her, grumblingly.

"I'm heartily ashamed of that sale," Jack said, gazing after them.

"Get out," Bob replied. "That old lady has got a good mouser, and that's an equivalent to her money."

Duncan, however, was not satisfied, for Jack received a note from him, which read as follows:

"You're a sharp young cuss, ef I do say it, an' when ye b'y any more cats o' me fer nothin', an' sell 'em back fer nine dollars apiece, jest let me know!"

"Josiah Duncan."

† Correction made as per Volume 3.

Notes

| 1 | The middle name, "Lytton," is given in Banner Weekly. II, July 12, 1884; VIII, September 27, 1890; XI, September 16, 1893; and elsewhere. |

| 2 | Mr. R. D. Locke, of Titusville, says that in 1874 Edward appeared to be about nineteen years of age, and in the Correspondents' Column of the Saturday Journal, No. 487, July 12, 1879, his age is given as "about 25."

† A visit to the old Wheeler homestead in Avoca, N. Y., to which I was taken by Postmaster Ory Wagner, June 27, 1954, showed that Edward L. Wheeler's parents and grandparents must have been well-to-do. The large and well-preserved house of semi-Colonial design stands in a broad valley of apparently good farming land, and is surrounded by a range of low, rounded hills. In some of the rooms the interior finish of door and window casings is as it was in Wheeler's day. † The homestead is described in A History of Steuben County, New York, and Its People, by Irvin W. Near, Chicago, 1911, 1, 485-88. |

| 3 | Mr. Clark W. Stryker, whose maternal grandmother was Edward L. Wheeler's sister, in a letter to me June 19, 1943, said "Sanger Wheeler was the sixth child of his parents; the other eight children were Chandler, Mary, Lydia, Charlotte, James Steams, Dorcas, Andrew Jackson, and Sophia. Herman Lewis was among the early settlers o£ the township of Wheeler, Steuben County, New York, just east of Avoca township. Both of Edward's parents are buried on or near the old Wheeler homestead, about five miles south of Avoca in the adoining township of Bath. |

| 4 | In the Saturday Journal, No. 429, June 1, 1878, Wheeler, in relating an incident in his life, said that he and his father ran a little store, then a branch of a bank, in Cashup, in Pennsylvania. I have found no other reference to this fact. The date must have been in the early 1870's. |

| 5 | "Barbara Wheeler, wid. Nathaniel S.," with the same address as that of Edward. While his father's name as given by Mr. Stryker was Sanger and here given as Nathaniel, it is probable that both given names were his, especially since the Directory gives the middle initial S. |

| 6 | †In the Saturday Journal (Star Journal), No. 497, September 20, and No. 498, September 27, 1879, he had a couple of articles on life in China: "Personal Observations of Messrs Locke and Karnes in China, boring for oil in the employ of the government." The story was based upon letters to Wheeler from his friend R. D. Locke, of Titusville, Pennsylvania. |

| 7 | From a newspaper clipping, probably from a Philadelphia paper, enclosed by Wheeler in one of his letters. A search by the Division of Vital Statistics of the City of Philadelphia failed to show a record of this marriage, such reports not being obligatory during the 1870's. |

| 8 | A letter from Wheeler, July 5, 1878, was dated from that town. |

| 9 | A letter published in the Young New Yorker, No. 6, December 30, 1878,8. |

| 10 | Correspondents' Column, Saturday Journal, No. 565, January 8, 1881. |

| 11 | This play was published by W. T. Coggeshall, Avoca, N. Y., in 1880. |

| 12 | Letter written by Wheeler, June 29, 1884.

† The illustration of Wheeler's letterhead of 1883, reproduced in Vol. II, page 295, was photographed by me from Wheeler's letter to R. D. Locke, of Titusville, Pennsylvania, dated June 29, 1884. In spite of the fact that Wheeler mentions on it that he has written 122 numbers of the Deadwood Dick novels, only 28 had actually been published when the letter was written and only 33 at the time of his death. † It is a curious fact that Wheeler's statement that he was the author of 122 Deadwood Dick novels should come so close to the actual number, for, including the ghost-written Deadwood Dick, Jr., stories, there was a total of 130. Was Wheeler's letterhead prophetic, or did Wheeler perhaps write outlines of contemplated stories which were or were not used by his ghost writers? Nowhere is there any indication that Wheeler had anything to do with the Deadwood Dick, Jr., stories, and there is much to indicate that he did not. † Wheeler died shortly after the final death of Deadwood Dick, Sr., which was related in Half-Dime Library No. 430. † For a more complete discussion of Cowdrick's authorship of many of the Deadwood Dick, Jr., stories, see Albert Johannsen, "The Deadwood Dick, Jr., Stories Not Written by Wheeler," in Dime Novel Round-Up, XXV, No. 298, July 15, 1957. |

| 13 | Philadelphia Directories:

1876. Edward L. Wheeler, reporter, h. 503 N. 39th. Babara Wheeler, wid. Nathaniel S. h. 503 N. 39th (This was Edward's mother, who apparently lived with him after his father's death.) |

| 13 | Edmund Pearson, Dime Novels, Boston, 1929, 107. |

| 14 | A slip-up on the part of the author, for he says, page 3, top of column 3: "The ringers were as white and soft as any girl's." |