| Home | Information | Contents | Search | Links |

|

And still they gazed, and still the wonder grew,

That one small head should carry all he knew.

OLIVER GOLDSMITH, The Deserted Village, lines 215-16

Thomas Mayne Reid, the son of Thomas Mayne Reid, a Presbyterian preacher, was born April 4, 1818, at Ballyroney, County Down, Ireland. He began to study for the ministry but soon abandoned that and in 1840 set out for America. He arrived in New Orleans and traded and hunted with the Indians, and hunted and trapped along the Missouri and Platte Rivers. For a time he taught school in Nashville, Tennessee, but in 1842 he went to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and in 1848 to Philadelphia, where he lived for about three years. His first publication was in the Pittsburgh Morning Chronicle, where some of his verse appeared in 1842 under the pseudonym "The Poor Scholar." In 1846 he joined the staff of the New York Herald as Society Editor, and in the autumn of the same year he was writing for the Spirit of the Times. During the war with Mexico, he was commissioned as second lieutenant in Burnett's regiment of New York Volunteers, and sailed for Vera Cruz in December, 1846. Vera Cruz taken, he was with his regiment in the storming of Chapultepec,(1) where he was wounded in the hip September 13, 1847. Shortly thereafter he was made first lieutenant. He resigned from the army May 5, 1848, and during the autumn and winter of 1848-49 lived with Donn Piatt in the valley of the Mac-o-chee, in Ohio; while there he wrote "The Rifle Rangers," which, however, was not published until 1850. He returned to New York in the spring of 1849, and sailed for Liverpool in June. He visited his home in Ireland, and then began in London the production of numerous novels of adventure. "The Scalp Hunters," his next story, appeared in 1851. In 1853 he was married to Elizabeth Hyde, a girl of fifteen, and removed from London to Buckinghamshire, about twenty miles from London. A daily evening paper, The Little Times, which he began to publish in 1867, was a failure, and in October of the same year he and Mrs. Reid went to the United States, arriving at Newport, Rhode Island, in November. Here he wrote "The Child Wife," which was published by Sheldon & Co. of New York. In their advertisement(2) they announced that "Captain Mayne Reid has now become an American citizen, and this is the first of his books in the sale of which he has any direct pecuniary interest. Protected by our laws, he now receives the regular copyright of an American author." Mrs. Reid(3) stated, in her biography of her husband, which is not always accurate, that "Frank Leslie's Paper paid him 8,000 dollars for the right of first appearance in its columns." She also said that The Fireside Companion paid him $5,000 for "The Finger of Fate." In January, 1868, he entered into an agreement with Beadle & Co. to write a series of dime novels for them, "The Helpless Hand" being the first.(4) This was followed by "The Scalp Hunters," a reprint, "The Planter Pirate" and "The White Squaw" in the same year, and "The Yellow Chief" in 1869. For "The White Squaw" he received $700 from Beadle, said at the time to be the highest price ever received by any writer for a dime novel. It was, however, not the highest price paid for the serial rights of a story, for Leon Lewis, Oll Coomes, and several other writers received more. Reid continued writing for Beadle for eight or nine years and, in fact, continued to send them sketches until his death. A magazine which he started in 1869, Onward, lasted only fourteen months. The next year he was confined to St. Luke's Hospital in New York for some time, owing to an infection of the wound he received in Mexico. On September 10, 1870, he was able to leave the hospital and sailed for England where he resumed the pen, writing short stories and revising some of his earlier novels. "The Death Shot" was also written at this time and appeared in The Penny Illustrated Paper. In October, 1874, an abscess formed on the knee of his wounded leg, and thereafter he was unable to walk without the aid of crutches. He was joint editor with John Latey of The Boys' Illustrated News from April 6, 1881, for ten months, and wrote for it "The Lost Mountain; a Tale of Sonora." About this time Reid's invention began to flag and he became less popular, so that he turned his attention to farming near Ross, in Herefordshire, although he also continued to write. His last novel, "No Quarter," a tale of the Parliamentary wars, and his last boys' book, "The Land of Fire," were published after his death, which occurred October 22, 1883. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

Reid wrote about seventy-five novels of adventure and many short stories and sketches.(5) His early romances are by far the best, but his stories for boys, early or late, are pretty poor.

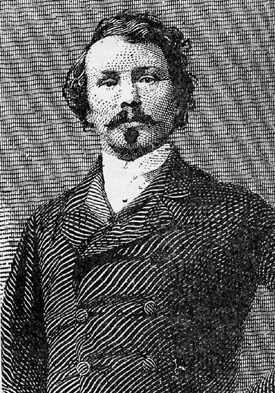

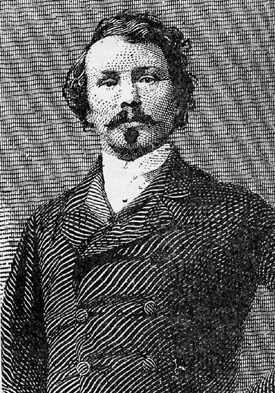

Reid was rather striking in appearance and somewhat foppish in his dress, addicted to lemon yellow gloves and clothes of unusual patterns and loud checks. He wore a monocle, and it may be that this gave rise to a story told by Pearson(6) that he had a glass eye, and that when Reid and some of his fellow authors went from the Beadle offices to a nearby place of refreshment, the Captain sometimes had the misfortune to lose his eye in his drink, and it became necessary for it to be fished out before conversation could be resumed.

REFERENCES: Elizabeth Reid, Mayne Reid, a Memoir of his Life, London, 1890, with portrait; Allibone, Dict. Eng. Lit., II and Supplement, II; E. P. Oberholzer, The Literary History of Philadelphia; Jeaffreson, Novels and Novelists, 1858, II, 387; The Saturday Journal, II, January 27, 1872, 1, with portrait; Beadle's Weekly, II, No. 53, November 17, 1883; II, No. 55, September 1, 1883; The Bookman (N.Y.), XIII, 1901, 58 (small portrait); Boston Evening Transcript, March 27, 1884; New York Tribune, October 23, 1883; New York Herald, October 23, 1883; The Writer, XIII, July, 1900, 112; Our Young Folks, III, 1867 (frontispiece portrait); Charles F. Lummis, Mesa, Canon and Pueblo, New York, 1925, 19; Fireside Companion, II, June 13, 1868, 4, 5 (portrait).

Dime Novels. Nos. 141, 150, 152, 155, 189, 373, 554,

559, 624

Saturday Journal. Nos. 10, 91, 97, 172, 205, 405, 446,

466, 513, 590, 600, 640

Beadle's Weekly. Nos. 1, 61, 205

Banner Weekly. No. 582

New and Old Friends. Nos. 1 (n.s.), 2 (n.s.)

Pocket Novels. Nos. 4, 10

Twenty Cent Novels. Nos. 5, 12

Starr's New York Library. Nos. 8, 12

Dime Library. Nos. 8, 12, 55, 66, 74, 200, 208, 213, 218,

228, 234, 267, 1026, 1072, 1080

Half-Dime Library. Nos. 4, 78, 87, 137, 239, 1122

Young New Yorker. Nos. 1, 22

Boy's Library (quarto). Nos. 2, 89

Pocket Library. Nos. 79, 702, 772, 725

SPECIMEN OF MAYNE REID'S STYLE

"The Land Pirates; or, The League of Devil's Island. A Tale of the Mississippi." Half-Dime Library No. 87, pp. 9-10.

For some minutes I remained thus irresolute, when it occurred to me that some one might stray out among the trees and discover me. A giant cypress stood near me, whose huge buttresses, surrounded by "knees" about my own height, offered an excellent place for concealment; and gliding silently into one of its dark niches, I took stand, cowering like a fugitive, who feels that the ruthless pursuer is upon his track and close to his hiding-place.

For some time I remained a prey to horrid apprehensions. After my experience of the previous night, I was justified in having them.

They were keen enough to keep me quiet. I made no more noise than was caused by my quick breathing.

For nearly an hour I stood in my "stall," between the two broad buttresses of the cypress, considering what I should do. I was still irresolute about retreating. The whole surface of the island was covered with palmettoes, whose stiff, fan-like fronds made a loud rustling when touched. I could not pass through them without risk of being heard. Why had I not been discovered while making my approach was probably because the boatmen were so busy about some matter that engrossed their attention. They were very near me—not thirty yards off, and but for the underwood I should have been certainly seen. If caught retreating, I should have given them the very opportunity they would desire—that is, if they meant to murder me.

Besides, I could think of no way by which I was to get off the island. I should gladly have gone back to the craft that had conveyed me thither, the drift-log, and once more trusted myself to the current. But I remembered that, on leaving it, it had become disentangled from the cypress, and resumed its course down the river. Even this waif was no longer available.

My next thought was to steal back to the side from which I had come, watch for some passing boat, hail her to bring to and take me off. But I knew there would be but little hope in this. I had reason to believe that the boats did not pass on that side. Though there the channel was wider, it was not so safe, and both steamers and flats kept to the other. I knew nothing of how the land lay, and I was apprehensive that by proceeding to make an exploration, I should be seen by the assassins of the flat. Even should a steamboat appear, I dared not hail with my voice, and any signal I should make would scarce be regarded.

My thoughts once more reverted to the dug-out. It was not likely the old craft would be disturbed by the crew of the cotton-boat, who had their skiff for a tender.

Concealed as the canoe was, under the fronds of the palmettoes, it might even escape their notice. I could wait till they took their departure, and then avail myself of it, to get off from the island. This, at length, became my determination.

I only hoped I should not be long detained; though I could form no idea of what was causing the detention of the cotton-boat. It did not appear to be an accident.

There was no sound of saw, or hammers, or anything like making repairs—only the hum of voices, with the trampling and shuffling of feet.

I listened to make out what was said, but could not. The conversation appeared to be carried on in a low tone, as if under restraint. There were three voices taking part in the talk, but Black's was the only one I could recognize. A second, I thought, was Stinger's; but the man was of a taciturn habit, and I only heard it at long intervals. The third was unknown to me.

Nor was any of them the voice of a negro. This I thought strange. Actively engaged as they appeared to be, if there were darkies employed at the work, their silence was inexplicable. I heard neither their chattering nor jocund cachinations.

After a time a fourth voice fell upon my ear, and in a tone that seemed to direct, or command. I was startled to think it was that of the planter, Bradley!

I listened more attentively than ever, straining my ears to the utmost. I could hear nothing but sound—the low humming of human voices, deadened in its passage through the thick shrubbery, and at intervals drowned by the shrieking of the grass-hoppers. For all this I could tell that there were four voices, one of them I was almost certain being that of Bradley.

It was with something more than curiosity that I interrogated myself as to what he could be doing there. I could only answer by conjecture. At first it seemed very strange. But then, I remembered that Bradley's plantation was not far off. Perhaps an accident had happened where and holding themselves unusually silent.

My eyes wandered to the hatchway of the little cabin, in which I had seen them asleep. Were they asleep still, or in the slumber of death?

My blood ran cold at the horrid suspicion—colder as I thought of its probability.

There was no sign of any negro. Stinger was alone seen by the steps of the caboose, still occupied with his scrubbing-brush.

My attention now became particularly directed to this man. What could be his object in washing the rough planks forming the roof of a flat-boat? Of what was he cleansing them? And why with such care? for he was down upon his knees, devoting himself to the task with apparent earnestness.

In seeking an explanation, my eye rested upon the "suds" chased to and fro before his brush. I saw that they were of a crimson color, tinged as if with blood! I saw this with astonishment, with trembling. I remembered what I had heard in the night—that I had believed to be a dream—the shot, and the shriek that succeeded.

Had both been real? Had murder been committed? And was Stinger engaged in eliminating the traces?

The blacks were no longer upon the boat. Where were they? Was it their blood I saw, and were their bodies at the bottom of the lagoon?

Horrid as were these suspicions, I could not help having them; and the thought that they were true gradually becoming a conviction, kept me quiet in the tree.

I remained silent on the limb of the cypress. Even the irksomeness of my seat did not tempt me to descend.

I was now sensible of being in a position of real peril. The men were murderers—all four of them—and one more crime would be lightly added to their last. Taking my life would be a step necessary tor their own safety, and I knew that if discovered I might expect but a short shrift of it. It needed nothing more to secure my silence.

Notes

| 1 | Reid's own story of the storming of Chapultapec appears in the Banner Weekly, No. 15, February 24, 1883, 2. |

| 2 | New York Tribune, November 28, 1868. |

| 3 | Elizabeth Reid, Mayne Reid, a Memoir, first edition, London, 1890, 239. |

| 4 | Reid's letter accepting the offer was published in an advertisement in the New York Tribune, January 11, 1868. |

| 5 | A translation of "Le Courier des Bois," by "Gabrielle Ferry" was published by DeWitt under Reid's name. See The Family Journal (Baltimore), II, August 4, 1860. |

| 6 | Edmund Pearson, Dime Novels, Boston, 1929, 265-66. |