| Home | Information | Contents | Search | Links |

|

Plausus tune arte carebat.

OVID: Ars Amatoria, 1.113

Anthony Paschal Morris was descended from, and related to, a long line of Americans prominent in the history of the United States. The first Anthony, a mariner, was born in London about 1630 and died in Barbados about 1655. His son, Anthony 2nd, was born in London in 1654 and died in Philadelphia in 1721. He was the first Quaker in the family, and his descendants, at least until the seventh generation, also belonged to that persuasion. Anthony 3rd, a brewer, was born in London in 1681 and died in Philadelphia in 1763. Anthony 4th, also a brewer, was born in Philadelphia in 1705 and died there in 1780. His son Samuel, a merchant, was born in Philadelphia in 1734 and died there in 1812. Samuel's son Isaac was born in Philadelphia in 1770 and died there in 1831, and Anthony, of the seventh generation, was born in Philadelphia in 1798 and died in 1873. Charles Wistar Morris, 8th generation, the father of the subject of this sketch, was born in Philadelphia in 1824 and died in 1893.

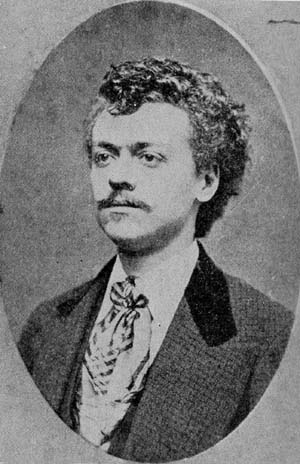

Anthony Paschal Morris, who signed himself Anthony P. Morris, Jr., to distinguish himself from an uncle, was born in Safe Harbor, in the Conestoga Valley, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, October 15, 1849. After leaving Andalusia College, in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in 1867, with no trade or profession, he spent his leisure in writing a series of sketches for the Washington Sunday Herald, and his first serial, "Lorilyn," ran for nine weeks in that paper. Being successful in writing, he abandoned his other work to devote his entire time to literature. In the spring of 1868, his "Rose and Thorn" ran for eight weeks in the same paper.

In 1868 he went into the agricultural and seed business with his father's uncle, Paschal Morris, of Philadelphia, but he continued his writing, in which he was more interested, and in the summer of 1869, when the Saturday Evening Visitor was started in Washington, he wrote for it a series of sketches, then a serial, "The Warning Arrow," for which he received $75. In the autumn of the same year, he became associate editor of that paper but retired when Hanna, of Richmond, assumed entire editorial control. In the meantime he had sadly neglected his seed business and, as he himself expressed it, it was "sunk." He next bought a farm in Prince George County, Maryland, and plunged into agriculture, but still continued contributing to various periodicals and to the country newspapers. About this time he signed a three year's contract to write for Beadle's Saturday Journal, and to it he contributed a dozen romances between 1871 and 1879. His last story for Beadle was Dime Library No. 343, published in 1885, although a number of his stories were reprinted after that.

|

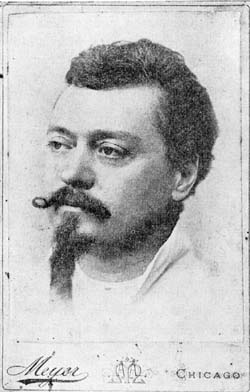

in Chicago between 1886 and 1895 |

Early in 1873 he quit farming and returned to Baltimore where he became connected with the Sunday Bulletin. He was married March 3, 1873, to Emma Teresa Van Hook, of Anacostia, D. C., and in 1874 or 1875 set up a printing establishment, A. P. Morris & Co., 26 South Broadway, which at that time was considered to be one of the best in Baltimore. In 1880 he removed to Howard County, Maryland, to run a chicken farm for a few years, but 1885 saw him back in Baltimore as a conveyancer.(1) The next year he came to Chicago and opened a store-brokerage business, calling himself a "Business Mediary." Presumably that business did not succeed, for already in 1886 his name appears in the Chicago Directory as a journalist, living at 753 Milwaukee Avenue, but there is no business address given. The next year he appears as a printer, still living on Milwaukee Avenue, a block away, at No. 668. Beginning the next year, with the Directory for 1889, Anthony's name appears as journalist in every annual directory up to and including 1895, except that in 1890 he is entered as "Foreman." He lived, during this time, at various places on the North Side, but his business address remained at 69 North Dearborn Street until 1893, the room number varying (35, 36, 49, 33) at different times and coinciding exactly with the various changes of room numbers of Warren T. Thomson, publisher of Heart and Hand. It is therefore almost certain that Morris was with this journal at least from 1888 to 1893. It is also likely that he was with Thomson during 1894 and 1895, for while the directory gives no business address, he was still rated "journalist," and Thomson remained at 69 North Dearborn. In the Directory for 1896, however, the names of Morris, Thomson and Heart and Hand have all disappeared.(2) Apparently Anthony shook the dust of Chicago from his feet in the latter part of 1895 or early in 1896, and about the same time was divorced from his wife. †

† Morris appears in the Berkeley City Directory (California) for 1921, where he is listed as a notary. He must, however, have arrived in California many years earlier, for a friend of Mr. P. J. Moran, who knew Mr. Morris, told Mr. Moran that Morris and some cronies used to meet occasionally at Temescal (located around Fiftieth Street and Telegraph Avenue, and now part of Oakland) for a social game.(†3) One night they "cleaned him out," and he got even by going home and writing a novel about the "Brigands of Temescal."(†4) It appeared June 4, 1898, as Old Cap Collier Library No. 756, and was entitled "Ten Pin Tom, the Contra Costa Detective; or, A Brush with the Brigands of Temescal." Mr. Moran's friend said the novel was written while Morris was living in Berkeley or vicinity, or perhaps in Temescal. He seems to have lived in that vicinity long enough to have made a lot of acquaintances before he wrote the novel. An earlier California story by Morris, entitled "Detective Buck and his Four Aids; or, The Tarantula Gang of San Bruno," appeared September 12, 1896, as Old Cap Collier Library No. 666. San Bruno is a few miles south of San Francisco, and his familiarity with the locality seems fairly good evidence that he was living in California as early at 1896. Perhaps he went to California directly from Chicago when Heart and Hand was discontinued about that time.

† In the Berkeley Directory for 1922, the name of Morris' widow, Mrs. Annie E. Morris, appears. She was his second wife, but her maiden name was not found. Morris died December 27, 1921,(†5) and in the Berkeley Gazette for December 27 and 28, 1921, his name appeared among the death notices.

Besides his novels for Beadle, Morris also wrote "Confessions of an Actress," "A Modern Monk," "Serpent Sin," etc. It is possible that he used the pseudonym "Nat Newton," for in his stort "The Ghouls of Baltimore," which appeared in Saturday Night, XIX, October 15, 1881, the hero's name is Nat Newton, and a short story in the same paper in 1882 is signed "Nat Newton" and is dated "Baltimore, November, 1880."

Morris had three children: Eleanor (1873-1874), Anthony Paul (born 1875, married to Cecil Fielding Fletcher of New Orleans, Dec. 4, 1894, died 1933), and Virginia (born 1879, married April 20, 1906, to Captain Alexander Shives Williams, of the U. S. Marine Corps, and died in 1922).

REFERENCES: The Journalist, III, June 19, 1886, 5; letter from Harbaugh to Dr. O'Brien, January 1, 1920, now in the New York Public Library; Chicago City Directories, 1886 to 1895; W. E. Price, Paper Capered Books, a Catalogue, San Francisco, 1894 (lists a few of Morris' books, not published by Beadle); Chicago Ledger, XIV, May 12, 1886, with portrait; Robert C. Moon, The Morris Family of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 1908, 5 vols.; in particular. III, 1012; Saturday Journal, No. 154, February 22, and No. 163, April 26, 1873; letter from Mrs. A. H. Binyon, Morris' niece, to me, 1943.

Saturday Journal. Nos. 59, 80, 90, 110, 125, 132, 143,

154, 170, 187, 201, 237, 321, 441, 454, 510

Braille's Weekly. No. 6

Banner Weekly. Nos. 476, 434, 559, 567, 575, 583, 597,

612, 700, 741

Fireside Library. No. 84

Starr's New York Library. No. 5

Dime Library. Nos. 5, 95, 100, 167, 185, 238, 260, 288,

306, 313, 334, 343, 357, 942, 951, 962, 982, 1028

Waverley Library (quarto). No. 767

SPECIMEN OF ANTHONY P, MORRIS' STYLE

"Azhort, the Axman; or, The Secrets of the Ducal Palace. A Romance of Venice." Dime Library No. 95, pp. 13-14.

Fortunately for Lady Perci, the drug which her own hands had introduced into the cake, fruit and wine, for the purpose of dosing Adria, was, as previously stated, only of sufficient quantity or power to stupefy a victim and render him or her pliant at the will of the person administering it. This, and the fact that she was enabled promptly to use the antidote for a poison so rare that none had known of it—until the published volumes of that renowned Florentine physician, Vidus, acquainted the old hemisphere with both the poison and the remedy—saved her from any severe results, and at the expiration of a few seconds she aroused, apparently thoroughly recovered.

Probably, had Azhort known the exact consequences to ensue upon his giving her the drug—instead of being convinced, by her evident alarm, that she was about to die—he would not so readily have found and furnished the white, antidotal powder; but, exulting in her mishap, would have said: "do this," and "do thus," and "follow so"—walking her to her own doom in the presence of Bal-Balla.

"Deathsman!" she ejaculated, very white and weak from the brief ordeal of having the drug counteracted at a moment when it was taking hold upon her system.

"Deathsman! I want no more—will have no more—converse with you. Let me send for that other and heavier purse promised. Then do you begone, by the same means you gained entrance here."

"'Sflames! not yet. A word or so more with you, Lady Perci."

Relieved of all anxiety for her life, just then, Azhort sat him down again upon the edge of the table, grinning and smirking as before.

Though time was fleeting, and he had much to do before the last boom of the fortress gun that was to signal the outbreak of the conspirators in Venice, he could not forego the jubilant desire to prolong this interview in the red room which evidently tormented a being parallel with himself in wickedness and intrigue.

"But I am weak. I can scarce sit. I must have assistance," she protested, snappishly, at the same time holding to the side of the sofa to steady herself in a transit of nausea and dizziness.

"Oho! And if I sat here and watched you slowly die, would it be worse than your treatment of Venturi Adello?

"I know naught of him."

"Come, thou, woman—we both know better than that. Your life is an open tablet to me, since you first bargained with me for the robbery and destruction of Rupert Riali, till now. Venturi Adello was admitted to this palace twelve years ago—it was a night of storm, you may recall quite well. He never went from here afterward. On the same night you sought the shop of a chain-forger and worker in metals and ores—his name was Barban. You brought Barban here, and Barban brought his furnace and tools, also a long chain. Oh! Now, what use had you for Barban and his tools, at an hour near midnight, in the Trienti palace, twelve years back? Tell me that!"

"All false—everything you say since your foul shape dared to snail and sneak here! I never knew of a man by the name of Barban."

"Shall I say to your teeth that you lie?" he exclaimed, scowling. "In the top of this palace there is a prison-cell. Barban, blindfolded, was led there"—the eyes, mouth, mien of the man seemed mustering their direst energies to appall her. "In the cell there was a man, drugged heavily. You are cunning and practiced in drugs, Lady Perci. Round the waist of the man, and round a column which is up there, you caused Barban to weld a chain. Afterward, in this very room, you plied Barban with drugs, got him into your gondola, and, when a convenient distance from the palace, you tossed him over to be carried out by the tide."

Lady Peri grew a trifle whiter. Her scarlet lips were compressed tightly. The words of Azhort searched, tingled and burned into her brain and drove away all vestige of her recent illness from the drug. He was startling her by revealing that he knew more of her life than she dared give to the world, though sustained by money and rank. But she was silent—silent and thoughtful as to how she might deal with this dangerous man.

"Barban, the chain-forger, did not die so easily," pursued the headsman, after a pause.

And had not Lady Perci such firm control of herself, she would have exclaimed, at this announcement:

"Ah!—did not die, when I filled him to his neck? Then the poison of Vidu's private memorandum—for which I paid the seller an enormous price—was a lie in itself.

But she said nothing.

"You left him to do his work, in so many hours, alone in the cell. He was through in half the time. Now, a prying knave was Barban. Some hours before you called him from above—he being an apt mechanic and an admirable rascal for getting at secrets—he learned that of which you never dreamed, with all your wit and wisdom: the Trienti palace had as many passages between its walls as on their outside!"

"Ah!" aspirated Lady Perci, becoming doubly intent at this.

"When you thought Barban had finished his task, you summoned him and brought him, again blindfold—and he was, by that time, laughing in his sleeve at your precautions—back to this red room. You had a fine feast prepared for him—oh! a delicious spread!—and a bag of gold on the table. A merry repast of cake, fruit and wine; something like this, no doubt," and he tapped here and there on the viands beside him. "By umph and by oracle! I see I am interesting you. So. Well, it was: 'Ha! ha!' laughed Lady Perci; and 'Haw! haw!" laughed the fool, Barban, sipping and tasting hungrily. Oh! a time of tickles and smiles. And when you had him helpless as a babe, though able to walk, you went arm in arm with the tipsy and poisoned fellow to your gondola. Finally, as I said, you toppled him into the water to drown, and thought that there perished the witness to the fact that you had a chained prisoner in the top of the palace. Ho! what will you say when I tell you that I rescued Barban?—for I was near and watching for the reappearance of Venturi Adello. Barban was nursed by me. He lived long enough to tell me all—the prisoner he chained, your poisoned feast, the secret passages! 'Sflames of Satan! I do not think you will ever secure the treasure of Rupert Riali—for which we made compact years ago—the hiding-place of which is known alone to Venturi Adello. I am satisfied that the man chained to the column is Venturi Adello. I am here, to-night, to see him. The treasure is for me—all mine—ho!"

Then Lady Perci uttered a fierce cry and sprung from the sofa.

Every bold, bad, resentful impulse of her nature surged upward in her heaving, burning bosom. A hundred fiends of mien and strength like Azhort could not have trammeled her now. An expression of consuming fury was molded in her face.

At a few bounds she reached and swung shut the heavy mirror. In a twinkling she had uncoiled the long-lashed whip from her arm, sending it, with one apt twirl, out full length over the carpet toward her enemy. "Come, deathsman!" she screamed, grasping the short. stout handle with muscles of frenzy and confronting him defiantly.—"Come, we'll play this game to its tragic end! You have discovered that I hold Venturi Adello a prisoner—ay, he shall continue so; mine only. I know you to be Sadrac, the pirate, on whose head a price was set eighteen years ago. Our battle is between ourselves. We will test if you can so easily wrest from me the treasure of Venturi Adello. Come on, and you will see a trick done with a strange weapon in a woman's gripe. Only over my dead body do you pass here. At. one cut of this whip I can sever your devil's head from its trunk! Come! Ha! ha! not yet, deathsman—not yet."

There is little doubt that Lady Perci, proficient as she was in handling the long-lashed and fearfully sinuous whip, could nearly tear a human head from its body at a single stroke. And even as she shrieked those words in the face of the man whose avowed purpose was to deprive her of a knowledge she had labored for twelve years to obtain from the prisoner of the secret cell, her strong arms had begun to whirl the stock round and round—as we have seen her do once before—and the supple lash was retreating, rising and forming circles above her head, to be let out in its resistless, gun-like snap.

"Satan of flames! Ho! As you say, there are two in this game!" gulped Azhort, sliding nimbly from the table edge.

One of the wine bottles, hurled by his giant's arm, shot through the air, and before Lady Perci could avoid the missile—enveloped and overbalanced as she was by the hissing coils of the lash—it struck her fairly upon the brow, momentarily stunning her.

She reeled—and once again the iron fingers of the headsman, who leaped forward and upon her with the quickness of lightning, twined around her windpipe.

He forced her backward and down, bringing her head to his knee, holding firmly by the throat with one hand, and with his other hand drew forth the bright-bladed and sharp knife he ever carried.

"Heaven save my soul!" groaned Lady Perci, in her heart; "I am about to be assassinated by the same knife that slew Cladius Atburno at my command."

While he held her helplessly thus, and seemed meditating whether or not to sacrifice her—his posture and glaring eyes both full of horrid menace—there was a loud knock at the door.

† Correction made as per Volume 3.

Notes

| 1 | The Baltimore City Directory lists him in 1886 as "Typewriter, 23 Lexington street, h. Howard st." |

| 2 | There are two other Anthony Morrises in the directories, all three appearing together in 1894, one a blacksmith, and one lamplighter, the latter appearing in 1896 as Anton Morris. Since all occurred together in one directory, they can not be confused with "our" Anthony. |

| 3 | †Letters to me from Mr. P. J. Moran, Oakland, California, August II and 22, 1950. |

| 4 | †It was, however, a poorly written story and was a great let-down from his earlier tales. |

| 5 | †Berkeley Courthouse records. |