| Home | Information | Contents | Search | Links |

|

Quando ullum inveniet parem?

HORACE: Carmina, 1.24.8

The life and adventures of Colonel E. Z. C. Judson, better known as "Ned Buntline," are so lurid and varied, and so much of the same character as those of the heroes of his own sensational novels, that it is impossible to write a fair account of him in the small space available here. A three volume biography would be none too large. The one biography that has been published is too fragmentary and incomplete, and the various notices in the biographical dictionaries are inaccurate and confusing. Even Judson's own accounts of his adventures are so conflicting that one must believe that he was sometimes amusing himself at his listener's expense.

Edward Zane Carroll Judson, the son of Levi Carroll Judson, was born March 20, 1821,(1) at Harpersfield, New York. According to his own account,(2) he was born during a terrific thunder storm, which seemed to presage his own stormy life. In 1826, his parents removed to Bethany, Wayne County, Pennsylvania, where his father taught school, wrote books,(3) and studied law, and in 1834 removed to Girard Square, Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, and there was admitted to the bar. Edward's father wished him to become a lawyer also, but Edward(4) preferred the sea to the law. A violent quarrel resulted, during which the angry father struck the son, and the latter, in November, 1834,(5) ran away to sea as a common sailor on board a West Indies fruit schooner, the "Mary C———," commanded by Captain Fred Skinner, a Baltimore bred sea captain. Here Judson messed with the captain but worked forward with the men. Some years later he rescued from drowning a number of persons who had been thrown into the water from a small boat which had been run down by a Fulton Street ferry boat in the East River, New York. For his bravery, President Van Buren appointed the seventeen-year-old sailor acting midshipman February 10, 1838, and he was ordered to proceed to New York and report to Commodore Ridgley for duty on board the United States sloop-of-war "Levant," attached to the West India squadron. Later in the same year, he served on board the United States frigate "Constellation" and on the sloop-of-war "Boston," also of the West India squadron. February, 1839, saw him on board the United States schooner "Flirt," a naval vessel co-operating with the army during the Second Seminole Indian War. On the recommendation of Captain A. J. Dallas of the "Constellation" and Commander E. B. Babbit, of the "Boston" he was warranted midshipman November 6, 1839, but his commission was antedated February 10, 1838, when his original appointment as acting midshipman was made.

It is said(6) that his fellow midshipmen refused to mess with him because he had been before the mast, so he challenged thirteen of them in a day, fought seven and wounded four, but was himself uninjured. Thereafter he was unmolested.

Before February, 1840, he was transferred to the schooner "Otsego," another vessel co-operating with the army during the Seminole War. He was still on that vessel March 16, 1841, but on the third of September of that year he was ordered to proceed to Boston and report on board the United States Receiving Ship "Columbus," where he remained until June 10, 1842, when he reported to Commodore Downes for duty on board the United States Frigate "Columbia," Home Squadron. A few weeks later, however, he was back on the Receiving Ship "Columbus." In April of the same year he went to the Receiving Ship "Ohio," and the same month was ordered to report to Commodore Shubrick for duty on the United States sloop-of-war "Falmouth."

In 1838 he had published anonymously, in The Knickerbocker,(7) sketch in which occurred a "pig episode," a much revised version of which later appeared, under the title "Eating the Captain's Pig" by "Ned Buntline," in a pamphlet of which no copy seems to have been preserved.(8) The two stories, however, differ greatly. Thereafter, Judson wrote continuously under the nom-de-plume "Ned Buntline."

In Havana, during the carnival season (Shrovetide, just before Lent) of 1839, he met his future first wife, a girl at that time 18 or 20, named Seberina,(9) and a niece of the Comtesa Escudero, and to her he was married in Cuba some years later. The exact date of the marriage is unknown, but he certainly had a wife in June, 1842, for he mentioned her in his letter of resignation from the navy, June 8, 1842.(10)

During the next two years it is said that he spent his time in the west roaming the plains and hunting, and for some time was in the Yellowstone region for the Northwest Fur Company.

In 1844 he started a magazine of his own, Ned Buntline's Own, in Paducah,(11) Kentucky, but he continued for some time longer to write also for The Knickerbocker. In December, 1844, there appeared in the latter magazine a story, "The Masked Ball," and in subsequent numbers several other articles appeared, including several installments of "Ned Buntline's Life Yarn," which was discontinued with the third number. It appeared later in book form.(12)

Judson soon discontinued his own magazine and in November, 1844, joined Lucius A. Hine and Hudson A. Kidd in publishing the Western Literary Journal and Monthly Magazine. The first two numbers were issued from Cincinnati and after that, until it was discontinued in April, 1845, from Nashville, Tennessee.(13) Judson was the editor of the periodical and wrote numerous editorials and several stories for it. Among other contributors were William D. Gallagher, Mrs. Caroline Lee Hentz, Albert Pike, Lyman C. Draper, J. Ross Browne, Donn Piatt, and others of like caliber.

In November, 1845, Judson was in Eddyville, Kentucky, and on the 24th he single handed captured two men wanted for murder and for this he received a reward of six hundred dollars.(14) In the same number of The Knickerbocker where this news item was given, is a rather ambiguous note to the effect that "Since the publication (of our last number) we have heard with deep regret of the death of the young and lovely wife of our correspondent," but it is not perfectly clear whether Judson or the correspondent who turned in the news of Judson's capture of the two murderers is meant. Apparently it refers to Judson. If so, then Seberina —— died in January or February, 1846, instead of 1841, as elsewhere(15) mentioned; consequently four instead of one year after his marriage to her. The item must refer to his first wife, for there is no record of a second marriage until 1848, and Judson at that time had not yet acquired the marrying habit.

On March 14, 1846, Judson shot and killed Robert Porterfield, in a duel at Nashville, Tennessee. Quoting from the Knickerbocker:(16)

We gather from the public journals that a difficulty recently occurred at Nashville, Tennessee, between our correspondent and Mr. Robert Porterfield, which led to a hostile meeting, in which, after three shots, the latter was killed, having been pierced with his antagonist's bullet in his forehead, just above the eye. . . . Judson was arrested, but the excitement was so great against him, that when he was taken before the Justice for examination, it became evident that he would be summarily dealt with. Some cried "Shoot him!" others "Hang him!" and a brother of the deceased shot at him several times: a number of shots were fired at him by others, and strange to say, he escaped all unhurt, ran off and hid himself in the City Hotel. Hundreds of excited persons collected around and in the hotel, and after searching some time, he was found, and endeavoring to escape, he fell from the third story to the porch. . . . The sheriff then took charge of him and conveyed him to prison. . . . "After he had been committed to jail," adds another and in some particulars different account, "in almost a dying condition from his fall, at about ten o'clock at night the mob, finding that he was still alive, broke into the jailed; maimed and almost naked, they threw him into the street, to be hung! He asked for a minister, which was denied him; he feared not death, but requested to be shot. . . . They took him to the square and ran him up over the rail of an awning-post; the rope broke and he fell; when he was taken back to jail, where he lies to die some time during the night." "And this horrible, infamous outrage," adds the Courier and Enquirer, with significant emphasis, "occurred in the streets, and was performed by the people of Nashville!"

In the next number of the Knickerbocker,(17) the account is continued:

We are glad to be able to state, that our apprehensions in regard to the death of Mr. Judson (our "Ned Buntline") had not at the last advices been realized. He writes us himself, under date of "Nashville, April 10th," although in a faltering hand, as follows: "Your April number has just reached me; and I hasten to tell you that I am worth ten 'dead' men yet. ... I expect to leave here for the East in three or four days. I cannot yet rise from my bed; my left arm and leg are helpless, and my whole left side is sadly bruised. Out of twenty-three shots, all within ten steps, the pistols seven times touching my body, I was slightly hit by three only. I fell forty-seven feet three inches (measured), on hard, rocky ground, and not a bone cracked! Thus God told them I was innocent. As God is my judge, I never wronged Robert Porterfield. My enemies poisoned his ears, and foully belied me. I tried to avoid harming him, and calmly talked with him while he fired three shots at me, each shot grazing my person. I did not fire till I saw that he was determined to kill me, and then I fired but once. Gross injustice has been done me in the published descriptions of the affair. ... I shall not be tried; the grand jury have set, and no bill has been found against me. The mob was raised by and composed of men who were my enemies on other accounts than the death of Porterfield. They were the persons whom I used to score in my little paper, Ned Buntline's Own. . . . The rope did not break; it was cut by a friend. . . . Mr. Porterfield was a brave, good, but rash and hasty man; . . . His wife is as innocent as an angel. No proof has ever been advanced that I ever touched her hand."

In April &dagger, 1846, Judson went to Pittsburgh,(18) and from there to New York,(19) where he became very active as an "isolationist"-"America for Americans," and "No British Need Apply," and was one of the founders of the United Sons of America(20) in Philadelphia in 1847.

On January 23, 1848, Judson was married to Annie Abigail Bennett in Trinity Church, New York. She divorced him September 29, 1849, and obtained the custody of their child.(21)

On July 22, 1848, appeared the first number of the revived Ned Buntline's Own, issued in New York City as a weekly, nationalistic paper (Fig. 222).(22)

The ever ebullient Judson could not keep out of trouble, and he was one of the leaders in the Astor Place Riot. William C. Macready, the English tragedian, was announced to play "Macbeth" May 10, 1849, at the Astor Place Opera House. Partisans of the American actor Edwin Forrest, who was also playing "Macbeth" in New York at the same time, announced a demonstration against Macready, and the following notice was posted in various parts of the city.

Workingmen, shall Americans or English rule in this city? The crew of the British steamer has threatened this city? The crew of the British steamer has threatened all Americans who shall dare to express their opinions this night at the ENGLISH AUTOCRATIC Opera House! We advocate no violence, but a few expressions of opinion to all public men. WASHINGTON FOREVER! Stand by your Lawful Rights!

American Committee.

The theater was crowded by Americans, British and police. When the curtain rose, not a word of the first act could be heard for hoots, groans, and hisses, while outside the Opera House the streets were filled with thousands of people, yelling and pounding on the doors. The National Guard was called and brought up a cannon filled with grape shot. They were greeted with showers of stones and soon fired into the crowd, killing some twenty-one rioters and wounding thirty-three more. Judson was arrested as one of the leaders of the mob, and was sentenced to a $250 fine and a year on Blackwell's Island. When he was released, September 29, 1850, he was escorted home by a torchlight parade of cheering admirers, and was banqueted by various political and patriotic organizations.

For the next few months he made a strenuous lecture tour, beginning in New York and taking in Middleton, Boston, Philadelphia, Wilmington, Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, and Norfolk. This was followed by a tour through the New Finland states and then to Pittsburgh, Allegheny, Sharpsburg, Cincinnati, and points west. †In 1851, for a short time, he edited the Prairie Flower, a Carlyle, Illinois, newspaper, founded by Benjamin Bond. (Frank W. Scott, "Newspapers and Periodicals of Illinois, 1814—1875." Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library, VI, Bibliographical Series, I, 1910. Listed under "Carlyle, Clinton County." See also Elmo Scott Watson's column "After Deadline," in The Publishers' Auxiliary, April 22, and May 6,1950.) Probably it was also about this time that he settled temporarily in St. Louis, for there is a record(23) of his having been a volunteer fireman in the Mound City Company, No. 9, which was in service from 1847 to 1857. How long he remained there is unknown, but in 1852 he was again back in New York †City, for in 1852—53, he was editing a weekly, The Empire State. In the number for August, 1853, he bade farewell to his readers saying that he intended starting a paper of his own, but he did not mention its name. Judson also in 1852 was one of the prime movers in reorganizing the "United Sons of America" under the name of the "Sons of '76" or "The Native American Party" (called the "Know-Nothing Party" from the universal reply given by members when asked about its tenents)(24) After some success at the polls, it went out of existence in 1856, and soon thereafter Judson bought himself a home in the Adirondacks, where he expected to devote his time entirely to writing, hunting, and fishing.

According to Chauncey Hathorn,(25) Judson was married a third time about 1857 to Marie Gardiner. Hathorn had recommended her to Judson as a housekeeper, and soon afterwards they were married. †She and her newborn infant died March 4, 1860, and were buried at the Eagle's Nest.(26) The bodies were later removed to the cemetery at Blue Mountain Lake, New York, and marked by a bronze plaque on an oval boulder which is inscribed:

Here lie the remains of

EVA GARDINER

Wife of E. Z. C. Judson (Ned Buntline)

together with her infant

She died at Eagle's Nest March 4th 1860

in the nineteenth year of her age

and was buried where a constant

desecration of her grave was inevitable

to avoid which the bodies were removed

to this place

and this monument erected in 1891

by William West Durant.(26)

The marriage to Marie Gardiner is not mentioned in the files of the National Archives, but the next, or fourth, marriage, is.(27) His wife was Kate J. or Catharine Myers, and they were married in Sing Sing, New York, November 2, 1860.

They were divorced November 27, 1871, and had four children: Mary Carrolita (Briggs), born 1862 in "Eagle's Nest", Irene Elizabeth (Brush), born 1863 in Chappaqua, N. Y., Alexander McClintock, born 1865 in Valhalla, N. Y., and Edwardina (McCormick), born 1867 in Chappaqua, N.Y.

On September 25, 1862, Judson enlisted in the First New York Mounted Rifles, and became Sergeant of Company K. He was transferred to the 12th Company, First Battalion, Invalid Corps, which subsequently became Company A, 22d Veterans Reserve Corps, and was honorably discharged as a private, August 23, 1864. Meanwhile he had been married for the fifth time, according to the records in the National Archives, to Mrs. Lovanche L. (Kelsey) Swart,(28) on January 14, 1863, in New York City, while on a furlough.

But Judson got himself into trouble again a few months later by overstaying his leave while on a visit to his wife, and was confined for a short time in Fort Hamilton, New York Harbor.(29) In order to get him back into the field, his wife, who complained of ill treatment, had him confined in the fort until he could be returned to his regiment in the South. However, the treatment could not have been very bad, for she visited him on the next and on succeeding days, and brought him a supply of stationery so that in the few days of his incarceration he is said to have written three novels.

Just one day before the surrender of Lee at Appomattox on April 8, 1865, Volume I, Number I of the fourth series of Ned Buntline's Own appeared, but it ran only a short time and Judson, suffering from numerous wounds and in ill health, went West to recuperate. In †1868 and †1869 he toured the Pacific States lecturing on temperance and Americanism.

As a result of meeting William F. Cody in 1869 at Fort McPherson, Nebraska, Judson wrote a series of novels about him.(30) The first story appeared as a serial in Street & Smith's New York Weekly, beginning December 23, 1869. It was entitled "Buffalo Bill, the King of Border Men." When the story was advertised November 25, the New York Weekly announced the "exclusive engagement of Col. E. Z. C. Judson, widely known by the production of over one hundred popular romances under the nom de plume of 'Ned Buntline'."

Cody(31) spoke of his first meeting with Judson, and described him as a stout gentleman, who looked like a soldier, in a blue military coat upon which were pinned "about twenty gold medals." These, he said, might be a good mark at which to shoot.

Judson's fondness for medals was also noted by a reporter for the New York Post,(32) who wrote:

Ned Buntline was in the fatigue uniform of the army, blue coat with brass buttons, and upon his blue vest twinkling decorations—the badge of the Sons of America, the head of Washington set on a gold shield with two American flags crossed above it, the original badge of the Order of United Americans which he organized, a golden hand crushing an enameled serpent, bequeathed to him by Congressman Whitney of New York when he died, a Grand Army badge and a Masonic pin. His gray hair is cut short. His only beard is a full white mustache. He weighs more than 200 pounds, I should think.

In 1870 or 1871 Judson went to the Catskills, Delaware County, New York, and built a home which he called "Eagle's Nest" after the name of his log cabin in the Adirondacks, and here he lived until his death. It was a large estate of some 120 acres, most of which was left in its natural state as a game preserve.

Judson was married for the sixth time, to Anna Fuller,(33) the daughter of John W. and Sarah Fuller, October 3, 1871, at Stamford, New York. They had two children, Irene A. Judson, born April 4, 1877, at Stamford, and Edward Z. C. Judson, Jr., born May 19, 1881, at the same place. After Judson's death, his widow was married to Eben Locke Mason, Judson's journalistic partner, July 9, 1888, in South Kortright, New York.

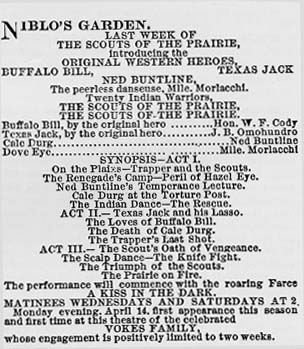

In 1872, Judson induced Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro to come to Chicago, where he wrote for them his play "The Scouts of the Prairie," later called "The Scouts of the Plains," in four hours. They opened at Nixon's, in Chicago, December 17, 1872, then went to St. Louis, and reached Niblo's Garden, New York City, March 31, 1873. Cody in his "Autobiography" said(34) that the Chicago Times(35) in its comments on the play remarked that if Buntline had actually spent four hours writing it, they wondered what he had been doing all that time! Buntline in the part of "Cale Durg" was killed in the second act, whereupon the Inter Ocean expressed regret that he had not been killed in the first.

Beadle reprinted a number of Judson's early stories, some of them under his well-known nom de plume of "Ned Buntline," but the six serials which had initial installments in the Banner Weekly Nos. 114, 127, 154, 172, 181, and 231, during the years 1885 and 1887, were written expressly for that paper,(36) No. 231 containing the beginning of the very last novel completed by him. He was at work on another, "Incognita," for the New York Waverley when he died. For the Banner Weekly he also wrote a number of short sketches, all under his own name, as was everything he wrote for Beadle, but for the New York Weekly he wrote under several signatures, including "Julia Manners."(37) "Mad Jack" was originally published under the pseudonym "Edward Minturn." "Clew Garnet" † may also have been his. "The Boy Gold Miner," in Good News, VII, June 24, 1893, was credited to "Charles H. Cranston." This name may have been wished on him by the publishers, for the story had previously appeared as by "Edward Minturn" in the New York Weekly, XXVI, June I, 1871, under the title "The Boy Miner."

†The Daily Graphic, New York, April 8, 1873. |

Buntline was a prolific writer. Ingraham(38) said of him that he once wrote sixty thousand words in six days, and he has at least four hundred novels to his credit. Besides writing prose and poetry, he also frequently lectured on temperance. He has also at least one hymn credited to him. Most of his tales are western-, pirate-, or sea-stories, full of adventures, not always plausible but at least thrilling, even though he is at times very tiresome. Prentiss Ingraham followed him closely in style. "The Black Avenger of the Spanish Main; or, The Fiend of Blood," published in Boston in 1847, may be of interest to Mark Twain collectors, for it is the original of the title adopted by Tom Sawyer when he and Huckleberry Finn were on Jackson Island playing pirates.(39)

Judson died at "Eagle's Nest" July 16, 1886, after great sufferings during the later years of his life from numerous old wounds. The direct cause of his death was probably a heart ailment.

REFERENCES: Fred E. Pond (Will Wildwood), The Life and Adventures of "Ned Buntline," New York, 1919, with portrait; Ned Buntline, Cruisings Afloat and Ashore, New York, 1848, 102 pp.; Ned Buntline's Life Yarn, New York, 1849, 192 pp.; Scribner's Dict. Amer. Biog., X, 1933, 237-39; Nat. Cyc. Amer. Biog., XIII, 1906, 194-95; Lamb's Dic. Biog., IV, 1901, 465; Kunitz and Haycratt, American Authors, 1938, 428-29, with portrait; T. Allston Brown, History of the New York Stage, New York, 414-18; Allibone, Dic. Eng. Lit.; L. D. Scisco, Political Nalivism in New York State, 1901, 88; Account of the Terrific and Fatal Riot at the New York Astor Place Opera House, May 10, 1849, pamphlet, New York, 1849; New York Tribune, December 15, 1856, and September 18, 1868 (oblt. F. Talmadge); New York Herald, September 20, and October 3, 1849; St. Louis Globe, December 27-28, 1872; New York Times, April 1, 1873; Boston Evening Transcript, July 17, 1886; Publishers' Weekly, XXX, 1886, 139; Turf, Field and Stream, July, 1886, 131; New York Herald, July 18, 1886; Banner Weekly, No. 197, August 21, 1886; New York Waverley, September 11, 1886, with portrait; Marquis James, "That Was New York, Action at Astor Place," The New Yorker, December 3, 1938, 42-50; Stewart H. Holbrook, "Life and Times of Ned Buntline," The American Mercury, LXIV, May, 1947, 599-605 (nothing new). Also various autobiographical items in Buntline's stories in The Knickerbocker for the years 1844, 1845, 1846, and elsewhere. Data from National Archives, etc., as given in the footnotes above. †See also Tid-Bits, III, December 12, 1885, 275, and Detroit Free Press, III, January 30, 1886, 390, for interviews with Buntline. An important contribution, recently seen, is Harold K. Hochschild's Township 34: A History with Digressions of an Adirondack Township in Hamilton County in the State of New York, New York, 1952. Chapter X, entitled "The Hero Maker," 114-48, deals with Buntline. There are many good illustrations, including several of Buntline, the one on page 143 being especially good. A very unusual photograph shows Ned about 1878 with a long, full beard. There are also photographs of Catharine Myers, Ned's fourth wife, and of Louisa Frederici Cody, Buffalo Bill's wife. Appendix D, pp. 459—62, is devoted to "Notes on Eagle Nest."

The following novels are credited in the bylines either to E. Z. C. Judson or to "Ned Buntline."

Dime Novels. Nos. 356, 588

Sixpenny Tales (London). Nos. 3, 6

American Tales. Nos. 51, 53, 54, 56, 61, 72, 79, 87, 91, 92

Starr's American Novels. Nos. 31, 140, 147, 165, 171, 176, 183, 188

Starr's fifteen Cent Illustrated Novels. Nos. 6, 11, 17, 20, 22

Beadle's Weekly. Nos. 114, 127, 154

Banner Weekly. Nos. 172, 181, 231, 588

Cheap Edition of Popular Authors. Nos. 20, 22, 25, 27

Starr's New York Library. Nos. 14, 16, 18, 23

Dime Library. Nos. 14, 16, 18, 23, 61, 111, 122, 270, 361,

517, 584, 621, 633, 657, 998, 1019, 1037, 1038, 1073

Half-Dime Library. Nos. 350, 1080

Boy's Library (quarto). No. 111

Pocket Library. No. 364

SPECIMEN OF "NED BUNTLINE'S" STYLE

"Thayendanegea, the Scourge; or The WarEagle of the Mohawks." Dime Library No. 14, chap. xviii and xix, pp. 12-13.

Seated upon the rock which was stained by the pure blood of gentle Leonore, the old Indian quietly remained until Guy Johnson came back.

"By the words you used, and the look upon your face, when you spoke of Sir William Johnson, my uncle, I suppose you hate him?" said Guy, as he stopped in front of the stranger, who did not rise at his approach.

"I do! What of that?" said the Indian, abruptly.

"I hate him, too—wish he was dead!" said Guy bitterly.

"Yet he feeds you—gives you clothes to keep you warm—you sleep under his roof!" said the Indian, and an expression of contempt flitted over his face, like a shadow upon a gray rock.

"I am his brother's son—he ought to do it!" said the latter evasively. "Besides, he wrongs me—has let a young Indian upstart supplant me in his love!"

"Who is this Indian upstart?"

"Thayendanegea, the son of one Dyagetto, the woman who brought him and his sister from the far-off Ohio; but I hear that she claims to be a Mohawk, for she is with them at one of their villages up the river."

If Guy had been looking at the Indian when he spoke, he would have been terrified at the sudden change in his countenance—the varied expressions there—when he made his statements; but the young man was looking back, to see it he had been watched or followed, and, when his eyes again met those of the Indian, the latter was as calm as he had been at first.

"And you say Sir William treats this young Indian with kindness?" continued the stranger.

"Yes; he has adopted him as a son, given him a horse, guns, and many presents. And he has placed his sister, like a lady, with his own daughters—dressed her as well as them!"

"But Dyagetto does not stay with her children?" "No; but she comes often to see them."

The old Indian did not ask any more questions, but sat and silently watched Guy, seeming to study his thoughts.

"You seem poor," said the latter, looking at the worn and ragged blanket and stained hunting-shirt and leggins of the old Indian.

"I am; but what of that?" replied the old man, drawing his blanket up proudly over his broad chest.

"I can better your fortune."

"How? You have nothing I want."

"You do not know that. Can you shoot?"

"Can a fish swim?" asked the Indian, in contemptous reply.

"Of course I know that you can shoot game; but if you had an enemy, could you shoot him?"

"If he was worth killing, yes!"

"Well, Sir William Johnson, you say, is your enemy. He is mine, also! I will give you a new rifle, hatchet, and knife, plenty of powder and lead, and new blankets and clothes, if you will lay in wait for him in the woods, and shoot him, the next time he goes to the fish-house!"

"He is your father's brother, eh?" asked the Indian, in a tone and with a look which would imply that he was seriously thinking of the proposition.

"Yes," answered Guy.

"And you love his daughter, the lily which you bruised this morning?"

"Yes, and when he is dead I will marry her."

"He brought you up since you was a little helpless boy, without father and mother, did he not?"

"Yes; but how do you know that? Have you ever seen me before this day?"

"Yes, yes, a hundred times, when you was too small to crawl over a log."

"Well, well, it matters not. What is your answer to my proposition?"

"That I thank the Great Spirit I am not a pale-face! Do your own murders! I am not an assassin!" said the old Indian, and, turning proudly upon his heel, he disappeared in the thick gloom of the grove, before the youth had recovered from the surprise into which the indignant and bitter tone of the scornful Indian had thrown him.

"By heavens, what a fool I am!" he muttered, when he found himself alone. "I should have killed the old wretch, for he possesses my secret thought and intent, and if he should make it known to my uncle, my every hope would be blasted. I will never venture out without my gun again, and, it I see him, I will shoot him as I would a wolf!"

"Shoot him, and I will shoot you!" said Thayendanegea, quietly, but firmly, as he stepped out from behind the trunk of a huge pine tree within a few feet of him.

"Why? Do you know him?" cried Guy, turning pale, and trembling from head to foot.

"No!" answered the young brave. "But he is an old man and an Indian—he is good, for he would not do a murder at your bidding! You could not hire him, as you did Ipisico, to do your wicked work! You are less than a dog—that would never bite the hand which fed it!"

"Why should you act the spy upon me?"

"Because your heart is blacker than mud! You are bad—too bad to live! I will watch every step you take, and, if you raise your hand or evil eye to one thing which I love, or is helpless, I will kill you as I would a snake!"

"I suppose you will go and tell my uncle of this matter!"

"I am no tale-bearer!" proudly replied the young Indian. "I can watch over him without putting more fear or hatred in his heart. But you must not cross my path, or study evil to him or his, or I will kill you! I have spoken, and I cannot speak a lie!"

Thayendanegea said no more, but, with a bitter look of contempt and scorn, turned upon his heel and went toward the mansion leaving the baffled nephew of the baronet in no enviable state of mind.

CHAPTER XIX

It was the custom with Dr. Daly, Mr. O'Whackem, and Mr. Lafferty, the baronet's secretary, to meet at twelve o'clock each day, or immediately after the schoolmaster had dismissed his pupils to their dinner, to partake of a lunch and its spiritual accompaniments, in a pleasant little refrectory adjoining the hospital, for these gentlemen all dined at the baronet's table at a later hour. And it was the occasion, generally, for a lively bit of gossip, for, all three being Irishmen, they could no more get along without talking, than a coquette without a string of beaux. Thus they kept their spirits up, while the spirits and the jokes went down.

"How does your new patient look this morning, doctor dear?" asked O'Whackem of Daly, as he poured out his glass of brandy, at lunch time.

"Very much as if a horse had kicked him," replied the doctor, with a smile, as he extended his hand for the bottle.

"He'll be apt to prefer your healing power to the heeling way of the ould stallion, I'm after thinking," said Lafferty, reaching in turn for the brandy.

"He's devilish impatient for a patient," said Daly, as he helped himself to a slice of cold tongue and a cold potato.

"He'll know better than to be so horse-style again!" said Lafferty.

"Och, ye blackguard, ye ought to be convicted, without judge or jury, of murder!" cried O'Whackem.

"Murder o' what, ye old pedagogue?" replied Lafferty, in his best humor possible.

"The king's English, Misther Quilldriver," said the schoolmaster, as he sliced off a bit of boiled ham.

"It's a pity that Master Guy hadn't got a touch of punishment from the baste," said Lafferty.

"Sure he got a good enough basting from me, I'm thinking!" said Daly, with a laugh.

"Why, his wasn't so much of an error, after all," said O'Whackem. "He might have been thinkin' of the neglected harp of poor ould Erin, when he called you 'a blasted lyre'—d'ye mind the point, now?"

"Sure the tune he harped on was a forbidden one, as far as I'm concerned," said Daly. "Pass over the bread, Lafferty, it ye're not too busy upon the hind shoulder o' that hog."

"D'ye know what you put me in mind of then, doctor?" asked Lafferty.

"No, sure—without it was that I considered ye better bred than I, and wanted to take a slice of me!"

"No, sure—it wasn't that at all. Ye put me in mind of the Lord's prayer, blessed be His name!"

"Wall, 'tis lucky I did, for it's seldom ye think of anything godly; but, for the life o' me, I can't see how I reminded ye o' what I know ye're not much acquainted with."

"Didn't ye ask for daily bread, ould thickskull?"

"Be jabers, I did, and you had me, boy. Pass along the brandy, for I thirst for the spirit!"

"Then ye ought to go and work in the corn-field awhile!"

"And why should I do that?"

"Doesn't the good book say 'hoe all ye who thirst,' I'd like to know?"

"Faith, you have me again! I wish ye'd take the fever and ague!"

"For why, ould pill-box? So ye could dose me and bleed me a bit?"

"No; I only want to see ye shook up a little; you're gettin' to be too smart on top, and too dull below. You want aqualising—just, you see, as I aqualise this brandy by putting a little drop o' water in it."

"And wakening the spirit! Sure it's not your advice I'll be afther takin', doctor dear."

"His advice is better than his medicine, I'm thinkin'!" said O'Whackem.

"Wait till you try 'em both, before you pass judgment," said the doctor.

"I'd rather see the sexton and gravestone-cutter first, so as to make all my preparations for a decent burial!"

"Let me write your epitaph!" cried Lafferty.

"What would it be, Misther Goosequill?" asked the schoolmaster.

"The like o' this," said Lafferty.

"Here lies ould schoolmaster O'Whackem:

A hard nut is he, But Satan will crack him."

"Faith, he'd throw you down as unsound an' not worth the crackin'!" said the schoolmaster with a laugh.

Thus these three worthies spiced their lunch, but it was soon over, and they returned to their different avocations, quite, refreshed in body and mind.

† Correction made as per Volume 3.

Notes

| 1 | Various dates and places have been given in biographical dictionaries for Judson's birth. The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, XIII, 194, gives August 16, 1822, as the date and Philadelphia as the place. Judson's daughter by his fourth wife, Mrs. C. Judson Briggs, in the New York Telegram, April 8, 1940, gave the date as 1820, and the place as Philadelphia. Pond, in "The Life and Adventures of 'Ned Buntline'," p. 10, says he was born at Stamford, New York, March 20, 1823, and the same date and place appear in Scribner's Dictionary of American Biography, X, 1933, 237. Allibone, Supplement, II, 927, and Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography give Philadelphia and 1822, and Judson himself in his "Cruisings, Afloat and Ashore," p. 41, says March 20, 1822. Probably more accurate than any of these is the date given in the records of the †Navy Department, Office of Naval Records and Library, Washington, D. C., on Judson's appointment as midshipman. He himself at that time gave his birthplace as New York state, and the date March 20, 1821. In his application for pension (WO 906 598), the date is not given, but the place of birth appears as Harpersfield, New York. When Judson was enrolled and mustered into service in the Civil War, the records in the Adjutant General's Office show that he himself stated that he was born in New York State, and that he was 37 years of age. This would make his birth year 1825, but it is probable that he understated his age by four years, so that he would not be thought too old for service. The date given when he was appointed midshipman is more likely to be correct, for at that time he had not yet begun to fictionize himself. Furthermore, the year 1825 would make him only 16 or 17 at the time of his first marriage, while his wife at the same time, according to his own account, was between 22 and 23 years of age. Actually, she was, if any, only a trifle older than he. |

| 2 | The Knickerbocker, XXVII, 1846, 37. |

| 3 | Some of his father's books were "A Biography of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence and of Washington and Patrick Henry," Philadelphia, 1839, "The Moral Probe, One Hundred and Two Common Sense Essays on the Nature of Men and Things," Philadelphia, 1872, and "Sages and Heroes of the American Revolution," Boston. |

| 4 | The Knickerbocker, XXVI, November, 1845, 432. Also Ned Buntline's Life Yarn, New York, 1849, 5. |

| 5 | Here is clear proof that Edward was not born in 1823, nor only eleven years of age at the time he ran away to sea, as stated in most of the biographies, for it is absurd to suppose that his father would try to make a lawyer of him at that age. Pond (p. 17) states that Judson related to a friend that he sailed around the world at 11, and became a midshipman at 13, but either Pond was mistaken or Judson was bragging. Actually, he was appointed midshipman when he was 17. |

| 6 | Pond, p. 16, quotes a fellow midshipman. |

| 7 | "My Log Book; or, Passages from the Journal of an Officer in the United States' Navy," The Knickerbocker, XI, May, 1838, 443-53. |

| 8 | This was later reprinted in Buntline's Cruisings, Afloat and Ashore, New York, 1848, 23-28. |

| 9 | Scribner's Dictionary of American Biography, X, 1933, 237—39, and Ned Buntline's Life Yarn, when it appeared in book form in 1849, give the name as †Seberina, but †Seherina, which may be a typographical error, was given in †Masked Ball, and the autobiographical sketch in The Knickerbocker, XXIV, 1844, 565-66. There is a letter from Lovanche L. Judson, a son by Judson's fifth wife, in the National Archives among material on file regarding a pension to the veteran, in which he said, "He told me that he was married about 1839 or 1840 to some one at St. Augustine, Florida. I can not recall her full name, but one name was Sevalina. He told me that she died within about a year after marriage." His fourth wife, Katharine Myers Aitchison, in a letter on file in the same place, said: "He had been previously married when a midshipman in Cuba, and his wife died a year later with her first child ... in Cuba." |

| 10 | The marriage thus probably took place later than Buntline himself thought, for in 1842 he had not yet been married a second time. |

| 11 | W. H. Venable, Beginnings of Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1891, 294. The Knickerbocker, XXIV, 1844, 102, gives the place of publication as Cincinnati. |

| 12 | Ned Buntline's Life Yarn. A Thrilling Story of the Sea, 192 pp., 8vo., New York, 1849. |

| 13 | Statements that the magazine was discontinued in consequence of Judson's duel with Porterneld are incorrect, for it had been out of existence for nearly a year before that time. |

| 14 | The Knickerbocker, XXVII, March, 1846, 277. |

| 15 | See footnote No. 9 in which Seberina's name is given. As mentioned above, she was still living in 1842. There is a legend that she was buried in the cemetery at Smithland, Kentucky. |

| 16 | The Knickerbocker, XXVII, April, 1846, 376. |

| 17 | The Knickerbocker, XXVII, May, 1846, 466-67. |

| 18 | Date line of a story in The Knickerbocker, XXVII, June, 1846, 544. †The Casket, Cincinnati, Ohio, I, April 29, 1846, 24, in a quotation from the Nashville Orthopolitan, stated that Judson "was discharged from prison yesterday and immediately left the city on board the steamboat California, bound for Pittsburgh, where his father resides." |

| 19 | Date line in the same periodical, XXVIII, December, 1846, 531. |

| 20 | This secret society was absorbed, in 1852, by the Know Nothing Party, but in 1868 it was reorganized under the name Patriotic Order Sons of America. |

| 21 | Afterwards she was married to Henry M. Calvert on February 16, 1867, in New York City. Judson's marriage was mentioned in The Knickerbocker, XXXI, 1848, 180, and it is also noted in the pension records in the National Archives. |

| 22 | This ran from July 22, 1848, at least to September 6, 1851 and probably longer, and was edited by Buntline even when he had his official residence in the city bastile. A third series ran from August 27, 1853, to April 15, 1854. †Judson started a new paper almost immediately under the masthead Ned Buntline's Sunday Paper, for No. 7, the only one seen, is dated June 18, 1854.1 do not know how long it lasted. A final series of his newspaper was begun on April 8, 1865, but it also was short lived. |

| 23 | History of the St. Louis Fire Department, St. Louis, 1914. |

| 24 | It was anti-Catholic, anti-foreigners, and advocated a pure American, anti-British, common school system, repeal or modification of the naturalization laws, and ineligibility of all but native Americans to public office. It was originally a secret society under the official title, "The Supreme Order of the Star-Spangled Banner." A. J. H. Duganne, the poet and also a Beadle author, was another of the organizers of the Know-Nothing Party. |

| 25 | Hathorn is quoted in Pond, pp. 57—58. |

| 26 | †There is some confusion as to whether Miss Gardiner's given name was Maric or Eva. The inscription on the monument, which was copied for me several years ago by Mrs. Doris Menzics of Blue Mountain Lake and was later photographed by me (June 21, 1954), gives it as Eva.

The first cabin at Eagle's Nest was demolished by Ned himself immediately after Eva's death and at once rebuilt. A very small portion of this second cabin and a part of Ned's dugout are preserved on a private estate and sheltered by a protecting roof. The well known "Eagle Nest" at Stamford, New York, came later. |

| 27 | National Archives, pension records of E. Z. C. Judson. In a deposition made October 17, 1892, filed with an application for a pension, Catharine Myers stated: "I have lived with Abram Aitchison since 1873; we were married by verbal consent." |

| 28 | National Archives, pension records, state that in a deposition by Lovanche L. Judson, the son ot Mrs. Lovanche L. Kelsey Swart Judson, made August 25, 1892, he said that his mother had had a prior marriage to Judson in 1853, in Hoboken, and that after living together for six months in Hoboken and several months on a lecture tour, Judson told her that the marriage was not legal, and she left him. Her former husband, L. A. Swart, had died December 31, 1851, in Eleroy, Illinois. There is no record of a divorce, but there seems to be a mix-up in the dates or else Judson was living with two wives at the same time. He was not divorced from Catharine Myers until November 27, 1871, and his fourth child by her was born July 27, 1867. Even his marriage to his sixth wife, Anna Fuller, on October 3, 1871, antedated his divorce from Catharine Myers by eight weeks, if the National Archives dates are correct. |

| 29 | Major T. P. McElrath's account of this confinement is given by Pond, pp. 74, 77-79. |

| 30 | Judson wrote a relatively small number of novels about Cody, although newspaper stories credit him with the great majority. It was Colonel Prentiss Ingraham who turned out the flood of Cody novels. |

| 31 | William F. Cody, Life and Adventures of Buffalo Bill, Chicago, 1917, 202. |

| 32 | Reprinted in the Banner Weekly, No. 197, IV, August 21, 1886. However, unlike the Duke of Wellington, he did not wear his medals on his nightshirt. |

| 33 | Records in the National Archives, pension applications, WO 966 598. |

| 34 | William F. Cody, Life and Adventures of "Buffalo Bill." Chicago, 1917, 265. |

| 35 | This is an error, for while the Chicago Times for December 18, 1872, had a half column report on the play, which ran from December 17 to December 21, nothing was said about Judson's tour-hour feat. Either this was just spoofing on the part of Cody, or the story appeared in some other paper. Perhaps Cody was indulging in a sly dig at Buntline. The Inter Ocean review I have not seen. |

| 36 | See blurbs and the "Correspondents' Column" in the Banner Weekly, Nos. 114, 127, 154, 172, 196, 231, and 316. |

| 37 | This pseudonym is also mentioned as one of Judson's in the Banner Weekly. No. 198, August 22, 1886, 4. |

| 38 | Prentiss Ingraham in the New York Herald, February 3, 1901. |

| 39 | The Introduction to "Tom Sawyer" gives the date of the story as "30 or 40 years ago," and since the book was published in 1876, that would mean 1836 to 1846. That Buntline's title may not show an anachronism in Mark's book, we must consider the date as about 1847. |