| Home | Information | Contents | Search | Links |

|

Was du nicht alles zu erzahlen hast!

GOETHE: Faust, Part II, line 3234

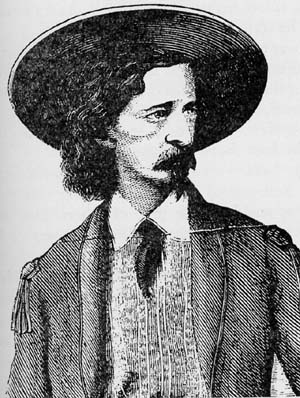

Samuel Stone Hall was born on a farm near Leominster, Massachusetts, July 23, 1838, and was educated in the schools of that place. Tiring of farm life, he ran away from home and started west. Not having money enough to pay his way, he became a "train butcher" on the trip to New York, where he took a job for a time as bell boy in a hotel. At the age of sixteen he went in a sailing vessel to Indianola, Texas, where he became a bullwhacker for Joe Booth. He then became one of Ben McCullough's Rangers. Although Hall was wiry and undersized, weighing but 125 pounds, with good features, dark eyes, and a gentle manner, he soon gained a reputation as a dead shot.

He was perfectly fearless, a hard rider and drinker, and associated with Big-Foot Wallace, Joe Ford, and others of similar notoriety. By them he was dubbed "Buckskin Sam," from the buckskin costume he always wore, and the name clung to him thereafter. He used it in signing the novels which he wrote in later years.

At the outbreak of the Civil War the Rangers were drafted into the Confederate army, but in July, 1864, he became a Union scout with Donaldson's Rangers, in the Army of the Southwest. When the war ended, he tried the hotel business, owning the Moodie House in San Antonio. Apparently it was not a success, for shortly thereafter we find him again with the Rangers on an expedition against Cortina, after his invasion of Texas.

Later, Hall returned to New England, but his reception by his family was not cordial. Sam liked to paint the town red, which shocked the staid New England village, so he departed for New York, where for several years he worked as a hotel clerk. Here he was found by his friends Buffalo Bill and Colonel Prentiss Ingraham, and they persuaded him to write up some of his personal experiences for Beadle. He did so, with the result that his first story, "Kit Carson, Jr.; or, The Crack Shot of the West," was accepted after some revision, and was published as No. 3, Frank Starr's New York Library. After that, he wrote many novelettes for Beadle and many short sketches for the Banner Weekly, among them a series on "Heroes and Outlaws of Texas," in numbers 112 to 121, in 1885.

It has been said that Hall employed a hack writer to revise his stories after he had written them out in full. How much truth there is in this is not known, but Hall certainly wrote at least the first draft of his stories, and apparently, when he became more experienced, wrote them entirely alone. It is very doubtful if any was written under his name by Ingraham, as claimed by some, for the style is entirely different. It is known that he kept a daily journal in which he recorded his experiences, and he kept a scrap book of newspaper clippings of prize fights, romantic occurrences, etc. Hall drew upon these for the stories which he afterwards wrote, although most of them were based upon his own experiences or observations. That Hall could write very good English is shown by some of his letters which have been preserved. Ingraham(1) himself said that Buckskin Sam "won some reputation as an author of Texan and Wild West romances."

In New York, Buckskin Sam again found too many temptations, so he removed to Wilmington, Delaware, in 1882, where lived a former Texan friend, George M. Dutcher, who, after a somewhat hectic life, had reformed and become a temperance revivalist. When Dutcher departed for places unknown, leaving his wife and several small children, Buckskin Sam stood by them and remained their sole support. During his last illness, pneumonia, Mrs. Dutcher took care of him until his death, February I or 2, 1886. He was buried in Evergreen Cemetery, Leominster, his funeral expenses being paid by Beadle and Adams.

REFERENCES: Prentiss Ingraham, "Plaza and Plain; or, Wild Adventures of Buckskin Sam," Boy's Library (quarto edition), no. 17, same as Boy's Library (octavo edition), no. 27. (Contains some facts and some fiction to make it interesting); Edmund Pearson, Dime Novels, 107—108; Boston Sunday Herald, February 15, 1886; Banner Weekly, IV, No. 173, March 6, 1886; A letter in the O'Brien collection in the New York Public Library, dated February 3, 1886, from E. M. Hoppes, Manager of the Wilmington Daily Morning News, to Beadle and Adams, asking for a contribution toward Hall's funeral; Chicago Ledger, XIV, March 10, 1886; Worcester (Mass.) Sunday Telegram, feature section, June 20, 1948. † The American Book Collector, X, March, 1960, 8 pp. including a bibliography of Hall's writings.

Saturday Journal. No. 436

Starr's New York Library. No. 3

Dime Library. Nos. 3, 90, 178, 186, 191, 195, 199, 204,

212, 217, 221, 225, 239, 244, 250, 256, 264, 269, 273,

282, 287, 293, 301, 309, 322, 328, 342, 358, 371, 511,

1035, 1070

Half-Dime Library. Nos. 234, 246, 275, 297, 307, 318,

327, 332, 344, 349, 357, 364, 375, 381, 392, 404, 414,

427, 442, 455, 634

Pocket Library. Nos. 189, 217, 248, 267, 285, 297, 304, 311, 317, 342, 348, 355

SPECIMEN OF SAM S. HALL'S STYLE

"Giant George; or, The Ang'l of the Range. A Tale of Sardine-Box City, Arizona." Half-Dime Library No. 246, p. 2.

"Hoop-la! Set 'em up! Sling out yer p'ison afore I stampede through yer hull business! I'm ther 'Bald-headed Eagle o' ther Rockies,' an' are a-huntin' sum galoot what's got ther sand ter stomp on my tail-feathers. Shove out a bar'l o' bug-juice afore I bu'st up yer shebang; fer my feed-trough are chuck full o' cobwebs, an' as dusty as Chalk Canyon. Hoop-la Don't be bashful, Don Diablo!" . . .

The speaker . . . stepped into one of the many hastily-constructed bar-rooms of Sardine-Box City, Arizona, holding in his hand a lariat which was drawn taut.

One instant his eyes darted glances around the bar, and then he turned about . . . addressing himself apparently to some person outside who seemed reluctant to enter.

As may be supposed, those in the bar-room were greatly astonished, not only at the words, but also at the manner and appearance of the stranger, as well as from the fact that he had seemingly gotten his lariat attached to some one who was being dragged about against his will.

All this was soon explained, for as the bar-room loungers gazed open-mouthed, the new-comer gave a powerful pull at the rope . . . and the next instant a most comical-looking burro, its huge, snuff-colored ears lying viciously along its neck, shot inside the door. This sudden movement slackened the lariat so quickly that the owner of the animal fell to the floor with a shock that shook the building.

Quickly rising to a sitting posture, the "Bald-headed Eagle of the Rockies," as he had proclaimed himself, gazed into the face of the burro which stood in the middle of the floor looking as innocent as a lamb.

"Wall, dod blast yer pecul'ar pictur', Don Diablo I wouldn't 'a' thunk yer'd 'a' made a spread eagle o' yer old pard, an' I'm dog-gon'd good mind ter drink alone. I've stood by yer mong 'Pache yells, dry cricks an' close feed, an' now ye're trying 'ter disgrace me!...

"Hoop-la! Did yer hear me whisper whisky? Dig ther bugs outen yer ears an' trot it out quicker'n an all gator gar kin skute, or I'll make toothpicks outen the hull caboodle!"

Accustomed to rough and desperate characters though the barkeeper undoubtedly was, it was evident that the man before him was a trifle more so than the average patron of the "O.K.", . . . consequently the vender of liquors, without a word, placed a bottle, together with glasses, before his strange customer. And a strange customer he certainly was.

He was tall, broad-shouldered—in fact a giant—with long unkempt hair, stray locks of which hung through holes in the crown of his old greasy sombrero. His father was covered with a heavy beard, with which huge bushy eyebrows claimed a brotherhood, mingling also with the hair above his huge ears.

Large hazel eyes glittered from beneath projecting brows, and proved by the unflinching way in which they met and held the gaze of others, that, notwithstanding his appearance, their owner was an honest, straightforward man.

His ragged buckskins were thrust into cowhide boots, and a strong wide belt was buckled about his waist; this supported a pair of old-fashioned army revolvers, and a large bullet-pouch, from which dangled an antelope-horn charger and the scabbard of his bowie.

The O. K. saloon was but a one-story structure, having some fifteen feet front on the street, and about twice that measurement in depth.

The bar was to the right of the entrance, extending along the side of the room; and beyond this were card-tables.

There were but half-a-dozen men present, mostly strangers, or counted as such by the citizens who were in the habit of congregating at a more popular resort. These were rendered speechless; dazed by the sudden entrance and strange address of the peculiar man with his peculiar beast.

The burro was not much larger than a Newfoundland dog, but a well-packed kiack upon its back caused it to appear much bigger, besides adding to its comical appearance.

When this strange individual had filled both the glasses, he wrenched the bowie from the plank, thrust the blade, edge upward, over his ear, the point projecting through a hole in the crown of his sombrero, and the handle hanging downward, apparently read; for use. This done, he grasped one of the tumblers, which in his hand seemed scarcely larger than a thimble, and approached the burro, opening its mouth and inserting the glass between its jaws.

The giant borderman then clutched his own glass from the bar, clicked the same against the tumbler in the burro's mouth, and yelled:

"Hyer's fun, Don Diablo! This are our spree, an' we pays for our refreshments. Hoop-la! Down she goes!"

Thus speaking, he gulped the liquor at a single swallow; while the burro slowly raised its head to the perpendicular, and allowed the whisky to pour slowly down his throat, to the amazement of the observers, who, however, refrained from expressing it.

"Does yer take me fer a humming-bird, that yer sots out sich a thingamy as thet fer me ter drink outen?" asked the giant, as he returned the glass to the bar. "Jest shove out a quart botde at me, an' hyer's ther pewter ter pay fer hit!" and he threw a gold eagle upon the counter.

Grasping the bottle, he walked to the side of the burro and placed it against the animal's shoulder; then, taking the nose of the beast in his hand, he bent its head into the former upright position. This done, he sprung backward ten paces, drew his revolver with a lightning-like movement, and fired, without seeming to have taken aim.

The cork Hew out from the botde, showing that the bullet had passed within two inches of the animal's ears; but the burro did not move until its owner stepped forward and removed the bottle from between its head and shoulder.

"Hoop-la! We're on a jamboree—a reg'lar jim-jamboree, Don Diablo an' ther 'King-pin Kiowa-killer,' ther cutest cuss o' ther canyons—thet's me! Hain't hit, Don?"

† Correction made as per Volume 3.

Notes

| 1 | Dime Library No. 834, footnote, page 8. |