| Home | Information | Contents | Search | Links |

|

Homo multarum literarum

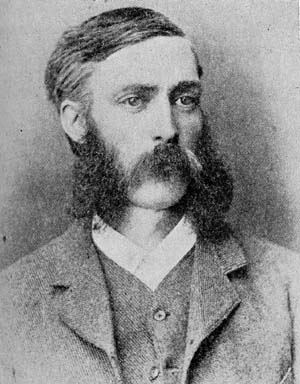

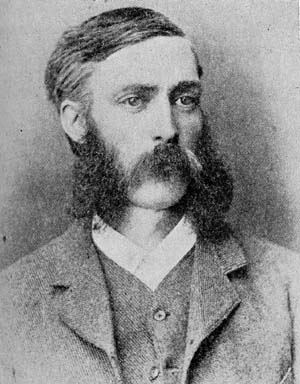

William Reynolds Eyster, a son of the Reverend David Eyster and his wife Rebecca Mary Reynolds, was born October 14, 1841, in Johnstown, New York. He received his preliminary education in the common schools and the Academy in that city, and later, when his parents removed to Pennsylvania, in the Seminary at Allentown. He entered Pennsylvania College at Gettysburg as a freshman in the second semester of 1856, was graduated at the age of 18 with the degree of A.B. in 1859, and two years later received his Master's degree for his literary work. He taught from 1859 to 1868, including five years as Professor of Latin and Mathematics in the Gettysburg Female Institute.

During the Civil War, from July to December, 1864, he served as first sergeant in Fullweiler's Independent Cavalry Volunteers. In 1865 he took up the study of law in the office of the District Attorney of Adams County, Pennsylvania, and was admitted to the bar of that state, March 25, 1869. He was a candidate for Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania the same year, but in the autumn he came to Kansas and homesteaded the SE1/4 Sec. 29, Twnshp 5, Range 5 East, in Washington County, and lived at Waterville and at Barnes, farming, until 1894. In the meantime he had been admitted to practice in the Courts of Washington County, Kansas, in 1872.

Eyster was married in Washington, D. C., December 19, 1871, to Sarah Elizabeth Copeland, of Maryland. In 1874 they went back to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where he took charge of the ticket and telegraph office and did legal work until 1887. He had been writing fiction since 1858, beginning while yet a student. His first short story was published about 1858 in the Great Republic Monthly. He was one of the early authors of Beadle's Dime Novels, his "Cedar Swamp" being No. 12 of that series, and appearing in 1860. "Free Trappers' Pass" appeared in 1864 as No. 4, American Tales, "The Haunted Hunter," in 1871 as No. 64 Starr's American Novels, and then nothing until 1881 when "Pistol Pards" appeared in Dime Library No. 145, and "Dandy Darke" and "Faro Frank of High Pine," in Half-Dime Libraries Nos. 190 and 210. Finding that literature paid, he gave up the Gettysburg ticket office in the spring of 1887 and returned to Washington County, Kansas, where he devoted his whole time to writing. He appeared quite regularly thereafter as a contributor to the Beadle publications as long as the firm bought manuscripts, that is, until 1897, and also wrote for The Nickel Library. He was, for a time, editorial writer for the New York Sentry and other papers in Pennsylvania and Maryland. Said C. F. Scott in an article on "Kansas Literature," "As a writer of everything, there is probably no one in the state better able to claim the title than Wm. R. Eyster."

In 1894, Eyster removed to Manhattan, Kansas, and in the autumn of 1897 to Topeka. In 1899 he was the silent partner of the printing firm Eugene L. Smith & Co., and on July 20, 1899, he became associated with A. H. Hoskins in the publication and editing of The State Record, a four-page, six-column weekly reform paper. He became both editor and publisher of this weekly on September 27, 1900, and was still so listed1 in the Topeka Directory for 1905. He was printer of the Topeka Plain Dealer, of which Nick Chiles was publisher, at least from 1907 to 1909, and perhaps longer. In 1915, the Topeka Directory listed him as a journalist. In the winter of 1916, he went to Butte, Montana, to visit a daughter living there, for he was fascinated by the early history of that city, which brought back to him the stories that he himself had written in former years for Beadle and Adams. He died in Topeka, July 16, 1918, and was buried beside his wife (March 25, 1847-January 27, 1903) in Maplewood Cemetery, Barnes, Kansas. His children were David Cameron, born in Kansas in 1873 and died in 1881, Alma Rebecca (Mrs. L. C. Solt), born in 1875 in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Charles Victor (named after Orville J. Victor, Beadle's editor), born in 1884 in Gettysburg, Helen Reynolds (Mrs. McKeivy), born in 1886 in Gettysburg, and Myra Virginia, born in 1888 in Washington County, Kansas.

According to Victor Eyster, his father used the pen name "R. Hunt Wilby."

REFERENCES: Letters from Mrs. L. C. Solt (Alma Eyster), C. V. Eyster, C. M. Hargcr of the Ahllene Daily Reflector, and George A. Root of the Kansas State Historical Society; Banner Weekly, No. 240, June 18, 1887, 4; Topeka, Kansas, Directories, 1899 to 1915; Charles F. Scott, "Kansas Literature," Topeka Daily Capital, August 11, 1889; Pennsylvania College Book., 1832-1907, Gettysburg, Pa.; Gettysburg College Alumni Record, 1932.

Dime Novels. Nos. 13, 569

Fifteen Cent Novels. No. 13

American Library (London). No. 55

American Tales. No. 4

Starr's American Novels. Nos. 64, 256

Beadle's Weekly. No. 128 (partim)

Banner Weekly. No. 529

Pocket Novels. Nos. 21, 62

Dime Library. Nos. 145, 160, 182, 192, 214, 229, 268, 300, 333, 344, 356, 375, 396, 402, 429, 459, 478, 503, 525, 533, 549, 558, 568, 578, 590, 603, 622, 634, 650, 659, 677, 687, 707, 718, 767, 783, 818, 828, 852, 867, 881, 891, 902, 916, 938, 977, 1069, 1091, 1093

Half-Dime Library. Nos. 190, 210, 838, 851, 888, 901, 919, 931, 945, 962, 969, 983, 1002, 1049, 1090

Boy's Library (quarto). No. 13

Boy's Library (octavo). Nos. 25, 134, 193

Pocket Library. Nos. 752, 207, 488

Popular Library. No. 43 (partim)

SPECIMEN OF WILLIAM R. EYSTER'S STYLE

"Harry Winkle's Long Chase; or, The Haunted Hunter." Boy's Library (octavo) No. 193, part of chapter III.

When Martin was within a few feet he paused, and the two gave a look at each other as though they would read the man confronting to the very soul.

It was Endicott who first broke the silence. He urged his steed onward a few paces, bent down in his saddle and extended his hand, at the same time exclaiming:

"Then it is you, Martin. I half-suspected as much when I first caught sight of you, and it gave me a shock. We meet as friends, I hope?"

Martin remained standing unmoved and as though he did not see the proffered hand, and answered, in a cool, careless tone:

"Yes, Endicott, it is I—no more, and no less. I know you've got nerves that are tolerably steady, so I won't show any wonder at your taking this meeting coolly; but it's kind of unexpected. You've drifted a long way out of your latitude to be floating along Back Load Trail. What's wrong in the East? Are the fools all dead, are the geese not worth the plucking, have the sheep come short in the wool crop, that you come here? Or are you in a stream that sets to the gold-diggings?"

"Bah, don't talk to me about the fools, geese and sheep that I've left behind me! Tell me how it is here. You and I used to understand each other pretty well, ay, and each other's secrets; so, come now; what's the best news in this heaven-forsaken region? Dick Martin doesn't locate here for nothing."

"No, he ain't located here for nothing; you're right. That something happens to be necessity. My luck in my little speculations ran out first, and I had to leave. As to what I'm doing here—that's not to be talked about. Maybe prospecting for gold; maybe Injun trading; maybe putting daylight through stray travelers and vamoosing with their traps; maybe any or all of these things—but not likely. I ain't here for nothing. That's all I can say."

"Martin, we have done business together many a time; we were allies, if not friends, and I want to know how the case stands now. I don't want to pry and peer into your private affairs. Maybe I'd be bringing something to the light that wouldn't stand it so well; but, I've heard somewhat of you as I came in this direction. Of course I didn't know it was you I heard the talk about, and of course there is a chance of what I heard being either true or false, with a little extra weight on the truth. You remember how we separated, and I don't think you have anything to complain of, or any charges of ill faith on my part to bring against me. Now, the question I want to ask is: Can we rely on each other as we could of old? A plain yes or no will make the best answer to the question."

"Well, Endicott, I haven't heard of you particularly, either good or bad, though I had an intimation that you were in the neighborhood. It makes no difference what reports have gone trailing toward the East, and I don't claim to know them; they're bad enough, no doubt. You ask a question, and if you must have an answer, why all I can say is: In some things, yes, in other things, no! Will that suit you, or shall I go ahead and explain?"

"What do you mean by yes?"

"I mean that, in the first place, I would rely on you just as much as I ever did, and not a particle more.

In the second, whatever you get my word to, that you can depend on my carrying through; but if you think to find me ready to promise to any and every mad scheme, you are very much mistaken."

"Anything that is honest, eh?"

A grim smile flitted over Martin's face at the mention of the word honest. It was gone in a moment, though, and he proceeded:

"Yes, anything that's honest. Now, what is it that you have to propose? I don't suppose you would have made so much of an introductory if you had not had something behind it."

"You are partly right. My motto is business first and pleasure afterward, else I would have had a thousand things to say with regard to our mutual lives in the past few years. Yet I hardly know what I would say. I did not seek you; yet, since I have met you, I want to know if I can count upon your assistance in a little matter which, springing up suddenly, has found me unprepared to meet it."

"Then you didn't hunt up Back Load Trail for any special reason?"

"No, indeed! It is just my lucky chance. The party I am with are camped half a mile over yonder. I left them from no very definable reason, and thereby met with an adventure that may have a great influence on my actions, perhaps on my whole future life. When we camped over there by the side of the stream, I thought it was but for the night, now I may linger in this neighborhood for a day or so. The question is, if I need a friend will you stand behind me?"

"What's this adventure, and how do you want me to stand behind you? If what I think is true, you may have more need of it than you think for."

"Well, Martin, I scarce know in what manner I would have you aid me; perhaps, after all, only by a neutrality. As to the adventure—I met with a woman."

There seemed to be nothing either astonishing or disconcerting in this revelation. After waiting in un broken silence for any remarks that Martin might feel inclined to make, Endicott proceeded:

"It was rather strange for a man to ride out of camp with no aim or object, and to stumble upon a woman; stranger, too, when that woman chanced to be one whom you had known long before, and for whom you had been long searching, and in vain. I do not know what may come of it. But I know what I want to. How is it? There is no one of our little party that I care to trust—if I need assistance within the next twenty-four hours, will you give it, and where can I find you?"

Martin looked up slowly and deliberately.

"It seems to me you're putting things on their old basis, what one of us plans the other is to help carry through."

"Why not? Neither you nor I have grown what the world calls better since then, and of course the under-standing would be now as it always was—nothing for nothing, all for whatever pays."

"No, I don't suppose we have grown much better; but there may have been a few changes. As to the woman you speak of, here is all I have to say. If you have any plans and carry them out openly and above board, no force, no underhanded means, no fraud, I'll not lay a straw in your way; maybe I can help you."

"If not?"

"This. Just you attempt the slightest bit of compulsion, or the first grain of trickery—try anything that's not honest, make a move toward abduction, or take a step toward foul play, and I'll lay you dead in your tracks."

"What do you mean?"

"I mean what I say. I give you fair leave and fair warning, too. I don't intend to interfere in anything she wishes to do, but I mean she shall not do what she doesn't want to do."

"Do you mean to say that you will exert any control over her actions?"

"Yes, just so far as to let her have her will. She's one of the few persons that I have cared for, and when time stops and the sea gives up its dead, you may, perhaps, see me go back on my dead sister's daughter."

* * * *

The speaker, who was an African of the unmitigated breed, caught sight of Winkle standing on the opposite side of the fire.

"Mass'r dis yer am Mister Bill Blaze. I knows him well, an' he's a fu'st-rate feller, ef he war a-goin' fur yer hoss. Nussed him up when he war tore all into leetle bits."

Winkle appeared to be somewhat recalled to life by this address of his sable attendant; and turning, looked the man thus recommended full in the face.

Blaze, once introduced, did not stand upon ceremony; but advanced across the intervening space, extending his hand as he walked.

"Yes, siree, I'm that identikle individool, Bill Blaze, jist frum the mountings! I kin trap more beaver, eat more burner, steal more hoss-flesh an' raise more topknots than any man frum here to the Columby River. I'm a blarsted bull-dorg an' a high-heeled snolligoster. I kin lick my weight in b'ar's meat, an' my name's Bill Blaze. Waugh!"

"I've heard that name before," said Winkle, taking the offered hand, "and you're welcome. I'm a little abroad just now, and don't feel like my own self—for I've seen a ghost."

"Thunder! You look kinder skeery; but ghosts ain't nothin'. I've seen more ghosts than any man a-trampin'. Had 'em for pards onc't. Fact. Three on 'em an' myself camped in a shanty down on Black-horn Lick fur nigh onto a month. There war a woman with her throat cut, an' a half-breed with his brains stove in, an' his skulp a-dangling 'ahind, an' a black b'ar with his back bruk. The way they tore around that 'ere shanty war nasty. Why, down thar on that thar Lick, ghosts war as plenty as ha'rs in yer head. An' yell? The catamounts got so 'shamed of their own mule music they packed their trapsacks an' got. Yer couldn't find a painter nigher ner fifty mile. No, stranger; don't talk to Bill Blaze about ghosts, fur he's bin thar!"

Winkle appeared to be little moved by this address. His face still bore marks of evident perturbation, and there was an absence of mind depicted in his manner and actions that seemed to strike Blaze as rather unwarranted. To some remark made he answered rather shortly; but he accepted of the hospitalities offered him, so far at least as to seat himself by the fire, and, in default of other entertainment, entertained himself by the sound of his own voice.

"No, ghosts don't bother this hyar hoss. Nor redskins nor grizzlies neither. I kin trap more beaver, kill more b'ar, shoot straighter, run quicker, jump further, lie faster, stampede more animiles, an' carry more pelts than any bloody bull-dorg ever invented. But, I'm the man without luck. I've wrastled with the old boy fur thirty years; he's got an under holt on me; but I'm dead game, I am! Luck or no luck, I'll hang like seventeen pair o' tongs and a last inch gamecock. Waugh!"

The negro listened to these announcements, if Winkle did not. He was accustomed to this style of thing, and had heard Blaze before.

"Mass'r Blaze, 'pears to me de bad luck ain't so mitey bad; I's t'inkin' it's t'oder way cl'ar. Any udder man'ud bin gone under—dun gone suah—ef he'd de half what you's had to go tru. You's allers a-sayin' you's nary luck, an' allers a-gittin' inter de wu'sted kind o' skrimdigers—an' still you am heah. What's de trouble now?"

"Wal, Pomp, I allow it's no luck as pulls me through, but just pure grit and muskle in this huyer hoss. I war camped out in a bully old spot last week; meat plenty, beaver to be had for the taken of 'em, and everything going along on a string. Didn't think thar was Injin within twenty mile, an' blast me, ef they didn't cum down an' clear us out quicker than the jerk of a dead deer's tail. Bob Short an' I war thar together, you see, an' Bob struck all right, but they got my old sorrel mare, an' all our provender, an' I just cum down from them are mountings after a chase o' four days, poorer ner Job's turkey, an' nothen left me but Slicer an' this huyer old shootin'-iron. An' this huyer very blessed night, as I were movin' along promisc'us, thar war a rifle-ball went sizz a past my head-piece, an' I squatted an' see'd two men a-talkin', an' found that bit o' lead warn't meant fur me, an' while I war a-listen,' sock cum somethin' right acrost me, an' hove a yell wuss ner forty catamounts fitin' in a small box, I know'd it war a copper-belly an' clinched. We hed it, pull an' hug a bit, an' then I got Slicer out. That thar red-skin won't cum a-pryin' an' a-peerin' down along Back Load Trace soon ag'in. Nary; not much; waugh."

The story of the trapper began to interest Winkle; he thought less and less of the ghost; he descended from the clouds and listened with earnestness to what the man was saying. He thought of the corpse that Martin and he had seen drifting down the stream, and believed that the Indian would not come prying and peering in that neighborhood soon again. Perhaps, too, this man might be of service to him? At any rate it would do no harm to meet him cordially.

"Then you are the man who had the tussle over there with an Indian? I heard the yell, saw him shoot into the stream, and went across to see what it was about. I was following your trail, when I came across a sight, or rather a sight came across me, that unhinged my nerves. But how came the difficulty with the Indian? What was he doing there? Is there danger from others that should be specially guarded against?"

"Yes, siree, I'm the man! The diffikilty perobably arove from his not keepin' both eyes peeled. He was so bent on hearin' that he couldn't take time to see, an' tumbled onto a hornet's nest. He clinched right in then by instink, an' as it war die dorg er eat the hatchet, I hed to let it into him, though I'd as ruther not. What he was a-doin' I dunno. Injin deviltry are various. Thar oughtn't to been a red-skin within fifty miles o' huyer. Thar may be a couple more on 'em or thar mayn't. What they'd be arter I can't say. Martin ought to know'd ef thar war any, an' I guess he's got his men out by this time a-lookin'."

Notes

| 1 | George Jenks (Bookman. New York, XX, 1904, 108-114) incorrectly stated that Eyster "is an editor in Denver today." |