| Home | Information | Contents | Search | Links |

The foolishest book is a kind of leaky boat

on a sea of wisdom; some of the wisdom will

get in anyhow.--O. W. Holmes, The Poet at

the Breakfast Table, chap. XI

UPON the unoffending head of Erastus Beadle has been heaped the opprobrium of being the originator of cheap, demoralizing, blood-and-thunder publications. As a matter of fact, cheap, paper-covered, sensational literature had been issued by various firms for more than thirty years before Beadle began his famous Dime Novels, and these early novels were even then spoken of as "yellow covered literature."(1) The innumerable story papers which were already popular during the first half of the nineteenth century also antedated the Dime Novels, and in them appeared for the first time many of the sensational stories which later were reprinted as nickel and dime novels.(2)

Not only was Erastus Beadle not the first publisher of cheap, "yellow-backed" novels, but, in spite of all hitherto published articles on the dime novel, he did not even originate the original Beadle's Dime Novels. For these the credit belongs to Erastus' younger brother, Irwin, as I shall show later. But while Irwin himself was not the first publisher of cheap paper covered novels, he was the first to issue them in continuous series and at a fixed price of ten cents, instead of issuing them sporadically.

In the very beginning, it may be well to answer the question: "When is a dime novel not a dime novel?" Using the term with the customary meaning of the middle 1870's and thereafter, the Dime Novels were not "dime novels," but the nickel "libraries" were! Popularly, the term had little reference to the price at which the booklets were sold, but it was applied especially to any sensational detective or blood-and-thunder novel in pamphlet form.

The deterioration of the "dime" novel may be said to have begun in the early 1880's, and they degenerated rapidly after the introduction of detective, gamin, and bootblack stories. The first Beadle detective story was written by Albert Aiken as a serial for the Saturday Journal and began June 10, 1871, in No. 65. Another by the same author began in No. 119, June 22, 1872, and one by Anthony P. Morris in No. 143, December 7, 1872. There was another by Aiken in No. 167, May 24, 1873, after which none appeared until December 30, 1876, when one by Charles Morris began in No. 355. There were three in 1877, and one in 1878. The next year they appeared in both the Saturday Journal and the Half-Dime Library. Excluding reprints, there were two in 1879, five in 1880, seven in 1881 and seven in 1882. The flood began the next year with 14 in 1883, and they soon overshadowed the Indian, western, and historical novels.

The original Beadle's Dime Novels were entirely different in appearance from the later productions. They were small, sextodecimo booklets of approximately 100 pages, with clear type and with orange wrappers upon which was printed a stirring woodcut in black. They sold for ten cents. During the early years of publication, the tales gave fairly accurate pictures of the struggles, hardships, and daily lives of the American pioneers. Begun less than half a century after the last war with England, they were intensely nationalistic, and if any stories ever burned with "the spirit of patriotism," it was in these books. For this reason they would doubtless not be popular at the present time with those who regard the United States Constitution as antiquated.

The nickel novels, which first appeared in the late 1870's, had, in the beginning, no wrappers. They were usually printed in small type, two or three columns to the quarto page, and had a black and white "action" picture on the front. Later they had wrappers printed in several glaring colors. The "colored-cover" quarto novels—it's unbelievable, but some collectors actually prefer them to the black-and-whites—contained Alger-like stories of poor boys who achieved fame and fortune, detective adventures, tales of Western bad men or scouts, or stories whose heroes were men of the Jesse James type. That is, many of the stories were much like many of our modern cloth-bound books except they were never nasty or sexy. Beadle, however, had practically ceased publishing before the colored-cover era began.

The original Beadle's Dime Novels were similar to the later quarto "broadleaves"(3) only in being cheap, in having paper backs, and in being spirited novels with very little philosophizing or flowery writing. Before the Civil War, the opening of the Eastern states, the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Indian wars were not long past, and the new generation heard at first hand the reminiscences of their elders. Then came the Civil War, and after that the opening of the West, with the exciting adventures of the pioneers in their trek farther and farther toward the setting sun, and their clashes with the justly exasperated Red Men who saw their hunting grounds forcibly taken from them.

The writers of the novels, if not themselves pioneers, were often familiar with Indian, hunter, and trapper adventures from tales told by the older men of their communities, and their stories had all the earmarks of verisimilitude. It was a lucky chance, perhaps, that led Irwin Beadle to begin his series with a tale of Indians and the frontier—perhaps his boyhood days in Cooperstown had something to do with it—and Erastus had the good sense to continue in the succeeding issues with many novels of the same type. That business competition later forced Beadle and Adams to let down the bars and permit the inclusion of detective and more sensational tales, was unfortunate. These later novels were all of a certain sameness, and most of them, like modem novels, followed a definite, though different, formula. Fortunately, the writers were not usually imitators of the romantic school, with swooning maidens, chivalry, rank and caste, sentimentality, and inflated speech. In spite of hurried production and lack of revision, most of them wrote very fair English, and never perpetrated such atrocities as "Aren't I?", so common in modern English novels.

Beadle's "Instructions" to prospective authors(4) indicate the type of stories he desired:

So much is said, and justly, against a considerable number of papers and libraries now on the market, that we beg leave to repeat the following announcement and long standing instructions to all contributors:

Authors who write for our consideration will bear in mind that

We prohibit all things offensive to good taste in expression and incident—

We prohibit subjects of characters that carry an immoral taint—

We prohibit the repetition of any occurrence which, though true, is yet better untold—

We prohibit what cannot be read with satisfaction by every right-minded person—old and young alike—

We require your best work—

We require unquestioned originality—

We require pronounced strength of plot and high dramatic interest of story—

We require grace and precision of narrative, and correctness in composition.

Authors must be familiar with characters and places which they introduce and not attempt to write in fields of which they have no intimate knowledge.

Those who fail to reach the standard here indicated cannot write acceptably for our several Libraries, or for any of our publications.

Considering the many simultaneous publications of the firm, it is no wonder that one lone editor could not always see that these rules were observed.

Beadle issued at different times about twenty-five series of novels, seven story papers and magazines, and innumerable handbooks, songbooks, dialogues, speakers, baseball books, etc. While the Beadles were prolific, they did not compare in productivity with Street & Smith who put out some fifty series of novels as well as many story papers, or Frank Tousey who produced over thirty series and four story papers. Most of the Beadle novels, except some of the love stories of the Fireside and Waverley Libraries and some reprints of English novels and of other American publishers whose rights Beadle had acquired for his "libraries," were written for the firm.

As mentioned above, the Beadle novels may be divided into two large groups; first, the booklet type novels, about 6 3/4 by 4 1/4 inches in size, enclosed in plain or colored wrappers, usually with an illustration on the front either in black line or in colors, and containing about 100 pages; and second, the broadleaves or black-and-white "thins," without outside wrappers but with a black line illustration on the front page, and either quarto or octavo in size; the quartos with 16 or 32 pages, the octavos with 32.

The booklet-type novels and the Half-Dime Library generally contained about 35,000 to 40,000 words, while the Dime-Library had from 70,000 to 80,000. The octavo broadleaves, such as the Boy's Library and the Pocket Library, contained about the same amount of reading matter as the 16-page Half-Dime Library, but the type was larger and there were 32 pages. When a novel originally issued in one series was to be reprinted in another and was too long, it was "blue pencilled," until it came within the allotted space. Usually the editing of the Beadle novels was fairly carefully done, although occasionally one senses that something is missing. Munro, in his Ten Cent Novels, was not so careful, and the hiatuses occasionally are great enough to cause the reader considerable headache; the object of his blue pencil seems to have been to cut out words regardless of continuity.

Except for the brief trial of New and Old Friends in 1873, the quarto form was first used in April, 1877, for the Fireside Library, and in May of the same year for the Dime Library. Perhaps Beadle and Adams were somewhat in doubt as to the reception of the new format, consequently the first twenty-six numbers of the Dime Library were issued under one of the firm's other names—Frank Starr & Co.—and with the address 41 Platt Street, the side entrance to the Beadle office, at 98 William Street, just around the corner.

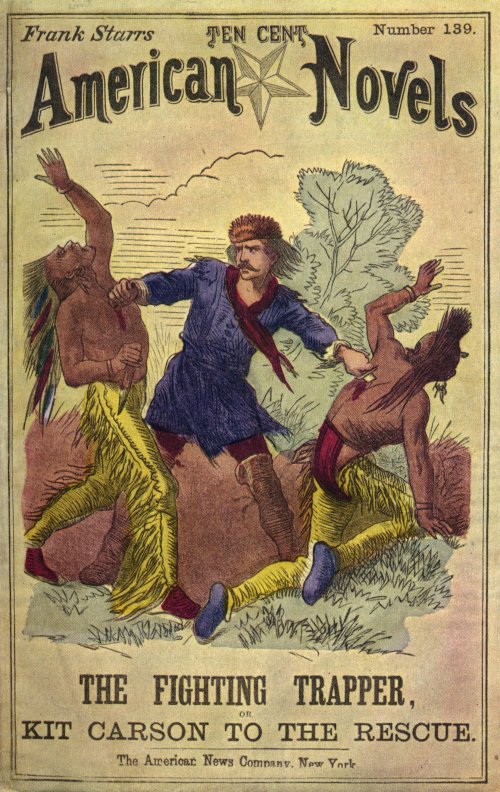

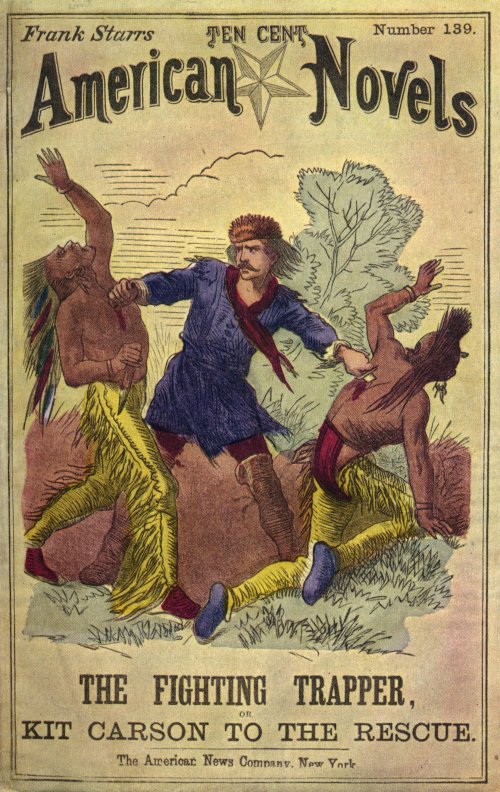

There are to be found in the Beadle novels adventures of such western characters as Wild Bill, Buffalo Bill, Texas Jack, Kit Carson, Daniel Boone, Lewis Wetzel, Simon Kenton, Davy Crockett, Big Foot Wallace, Calamity Jane, California Joe Milner, James Capen Adams, Micajah and Wiley Harpe, Simon and James Girty, Joaquin Murietta, Captain Jack Crawford, Major Lillie, the Powell brothers, and many more; and while the adventures are to a great extent fictitious, many of them, except perhaps the exploits of Buffalo Bill, which are so numerous that they could not have been performed by him had he lived as long as Old Parr(5) and Henry Jenkins(6) combined, are based on facts. But even when pure fiction, the adventures had to be plausible to satisfy the many readers who were familiar with western conditions. A story told of Kit Carson is amusing, even though the picture upon which it is based (Fig. 3) shows considerably less action than that mentioned in the tale.

In one of the Beadle novels, Carson was depicted as slaying seven Indians with one hand, while he clasped a fainting maiden with the other. When Carson, an old man, was shown the picture, he adjusted his spectacles, studied it a long time and finally said: "That there may have happened, but I ain't got no recollection of it."(7)

In general, each novelette was complete in itself, although there were many "companion stories" which were not really continuations but which related further adventures of the principal characters. Popular subjects often ran through many issues. Thus the "Deadwood Dick" novels ran through thirty-three numbers(8) of the Half-Dime Library. After Wheeler had killed his hero for the last time, the publishers were obliged to continue the series with "Deadwood Dick, Jr." as a substitute. The interest flags, however, although the series must have been popular, for it ran through ninety-seven numbers, thus even longer than the first. Other popular series in the Half-Dime Library were the "Violet Vane" stories by William G. Patten, which ran through eight numbers; Cowdrick's "Broadway Billy" novels in thirty-nine numbers; Ingraham's "Dick Doom" stories in sixteen numbers†; and Browne's "Dandy Rock" stories in seven. In the story papers and the Dime Library there were sixteen "Dick Talbot" stories, twenty-four "Joe Phenix," thirteen "Fresh of Frisco," and so on. The adventures of "Buffalo Bill" were told in one hundred different tales in the journals and in the Dime and Half-Dime Libraries, and they were printed and reprinted innumerable times in later years in the colored-cover series of other publishers. In fact, there were several "libraries" devoted entirely to the imaginary exploits of this popular hero. They were also printed in somewhat altered form and with additional stories, in the bulky pulp paper duodecimos which are still obtainable.

| 1 | "Riding on the cars through Michigan today, we have been half amused and half pained to see with what avidity "yellow covered literature" is here as elsewhere, devoured by travelers. . . . Numbers of well dressed and sensible looking ladies and gentlemen, with foreheads of respectable dimensions, have busied themselves for hours today ... in perusing, page by page, the contents of some shilling romance by [J. H.] Ingraham or some other equally stale and insipid novelist." |

| This quotation is from an editorial in the Western Literary Messenger, VIII, No. 16, May 22, 1847. The words "yellow covered literature," being in quotation marks in the original, suggest that the term was already in common use at that time. | |

| 2 | Among these early story papers may be mentioned Cauldwell, Southworth & Whitney's New York Mercury, begun in 1838; Ballou's Flag of Our Union, begun in 1845; Moses & Dow's Waverley Magazine, 1846; Robert Bonner's New York Ledger, 1855; Street & Smith's New York Weekly, 1855; and Frank Leslie's Stars and Stripes, 1859. The Youth's Companion, begun in 1827 by Nathaniel Willis, the father of N. P. Willis, the poet, was at that time a rather washed-out-appearing, four-page paper for young children, and cannot be classed with the red-blooded story papers. |

| 3 | There seems to be no suitable term for the 16- to 32-page quartos and octavos to distinguish them from the booklet type novels. "Thins" has been suggested, but it is not euphonious, and "broads" and "Hats" have other connotations. "Brochure" is too broad a term. I am, therefore, for the sake of brevity, coining the word "broadleaves." † Unknown to me, the word 'broadsheet' had previously been used by R. H. Shove, Cheap Book Production in hte United States: 1870 to 1891, Urbana, Ill., 1937, 7. |

| 4 | These instructions have been repeatedly published, e.g., in an editorial "An Interesting Chapter in American Literary History," Banner Weekly, VIII, No. 369, December 7, 1889. Also ibid., VI, No. 266, December 17, 1887. |

| 5 | Thomas Parr is said to have been born in Salop in 1483, and to have lived as a small farmer at Albersbury, near Shrewsbury, England, where he died † November 14, 1635, aged 152 years and nine months. He married his second wife when he was 120 years old, and had a child by her. |

| 6 | Henry Jenkins is said to have been born in 1501 and to have died December 6, 1670, aged 169. See William Hone: Every-day Book. for December 6, 1838, II, 1602, where his portrait is given. |

| 7 | Happy Hours Magazine, March—April, 1930, 3. |

| 8 | Half-Dime Library No. 430, the last of the Deadwood Dick, senior, stories, is incorrectly marked the 35th of the series. |