These illuminated leaves were acquired by the library in 2003. They are regularly used for teaching purposes at all levels. They are also available to anyone who is merely curious. If you are interested in visiting the library to view these leaves in person, please, drop by or contact us!

Please Note: The sizes of these images were adjusted to fit the computer screen and are not to scale. Click on the thumbnail versions to see a larger picture. You can return to this page by using the "back" button on your browser.

All of the images below are of single leaves --2 pages from a book, with a front (recto) and a back (verso). Originally, these leaves were all part of complete books.

Books during the medieval period were typically made of vellum (also called parchment), or, occasionally, especially during the later medieval period, paper. The cost of a book was dependent upon its size (both in height and in number of pages), and how much decoration it had (the more illustrations and illuminations, the more expensive the book). "The production of books was a collaborative enterprise involving co-operation between different crafts: parchment-maker, scribe, illuminator, and binder, together with, in many cases, a bookdealer who took orders from clients and oversaw the making of the final article" ( 1).

Before 1200, books were generally produced in monasteries. However, as universities in cities like Paris, Bologna and Oxford began to grow, the demand for books outgrew the abilities of the monasteries to produce them, and lay people stepped in to fill the gap. By 1400, most manuscripts were not produced in monastery scriptoria, but by professional book workers.

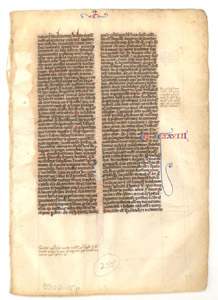

This small Latin Bible, which was produced in France in about 1250 A.D., measures approximately 4 inches across. Click the image on the right to see an enlarged view next to a ruler in order to better see its actual size. This leaf is from the book of Acts, Chapter XXXVIII. This particular item features some basic decorative initials, which show the reader the major divisions of the text. Typically, there was a hierarchy for the initials--the more important the text break, the fancier the initial. While in the early years of book production, the initials were added by the book's scribe, beginning in the thirteenth century, specialists would fill in the initials in the spaces left blank by the scribe. Red and blue were common colors -- these initials are often called "rubrication". In the fifteenth century, a preference for purple ink emerged. ( 3) Because of its size, and the level of decoration, this was most likely a relatively inexpensive Bible when it was produced. This particular leaf has some staining, possibly from water damage.

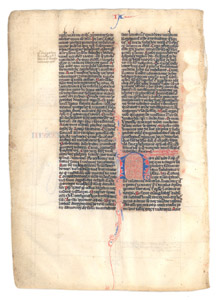

This 13th century leaf, from a Latin Bible produced in Paris, is roughly contemporary to the one above--but was likely slightly more expensive, since it is bigger, and features historiated (initials with pictures in them that usually relate to the text) and illuminated (decorated with gold or silver leaf) initials. This leaf has pen flourishing on the recto and the verso has an illuminated initial in the first column and a historiated initial depicting King Solomon in the letter "O" in the second column. The passage is from the opening of the book of Ecclesiasticus (Ecclesiastes).

This example is from a Book of Hours from Picardy, France, possibly Amiens, from approximately 1325 A.D. It has two historiated initials and a total of five decorated initials.

Books of hours are worship books used by regular people (not members of the clergy), as devotional items, to help with their daily prayers. They were held in the hand, and the illustrations were admired; they were not really used for reading the text. The text itself includes the standard prayers and psalms that are to be recited during the 8 different "hours" of the canonical day. ( 4)

Books of hours were the first "popular" books, owned in large numbers by ordinary people, not just scholars or monks. They were also highly prized status items, proving the wealth of their owners through the richness of their illustrations and bindings. ( 5)

A decorative leaf from a Breviary in Latin dating to around 1400 A.D. from Northern France is shown above. A breviary is a book of the daily Divine Office in the Catholic Church, used primarily by priests. It contains the texts used for funerals and saints' days, but not the Mass or Communion services.( 6)

The large blank space above the text is unusual. It is possible that an illumination was planned but never executed. ( 7)

This image is of a full-page miniature painting of the Crucifixion from Northern France, from around 1450 A.D. This leaf was originally in a Book of Hours.

This leaf is from Northern Germany, possibly Hildesheim, from around 1524 and is from a Psalter and Prayerbook in Latin, with a gold leaf border. A Psalter is a book of Psalms, and could have been used by members of the clergy or lay people ( 8).

This leaf is from a Book of Hours in Latin from France, possibly from the cities of Tours or Paris, from about 1530 A.D. This example has several decorated initials.

The design of this leaf is similar to two leaves offered for sale by Sotheby's in 2003, associated with "Dr. Myra Orth's so-called 1520s workshop." The most famous example of this workshop is the Doheny Hours, sold in 1998 by Sotheby's. The device of the knotted rope and the restrained colors used may indicate "that the patron was a member of the Cordelieres, the order of Franciscan Tertiaries to which the women of the French royal family belonged."( 9)

Notes

1. Watson, Rowan. Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers: An Account Based on the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: V & A Publications, 2003, p. 12.

4. de Hamel, Christopher. A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. London: Phaidon Press, 1994. p. 13.

6 Glaister, Geoffrey Ashall. 1979. Glaister's Glossary of the Book. Berkeley: University of California Press,70.

7 van Dijk, Ann. 2004. Personal Communication with Kay Shelton. DeKalb, Ill. January 23, 2004.

9 Sotheby's. Western Manuscripts and Miniatures, London, 2 December 2003, Lot 28.

The library has many resources about illuminated manuscripts and their makers available. You can find more books like these by doing a "Browse subject" search in our online catalog under "Illumination of books and manuscripts".

Alexander, J. J. G. (Jonathan James Graham). Medieval Illuminators and Their Methods of Work. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Call Number: Reference ND 2920 .A44 1992

Backhouse, Janet. The Illuminated Page: Ten Centuries of Manuscript Painting in the British Library. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.

Call Number: ND 2920 .B325 1998

de Hamel, Christopher. A History

of Illuminated Manuscripts. London: Phaidon Press, 1994.

Call Number: ND2900 .D36 1994

Watson, Rowan. Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers: An Account Based on the Collection of the Victoria and

Albert Museum. London: V & A Publications, 2003.

Call Number: ND 3310 W387 2003

The illuminated manuscripts that you see above were purchased by the library in 2003 through the kind auspices of the Fiends of the Northern Illinois University Libraries. RBSC was assisted in selecting the leaves by Professor Ann Van Dijk, from the department of Art History. Many of the leaves were digitized by Charles Larry, Head, Social Sciences and Humanities, University Libraries. The original research on the leaves was performed by Jessica Witte and Kay Shelton.